Benjamin Bratton | Machine Vision

Keywords: algorithms, Benjamin Bratton, Black Stack, computation, data issue, Internet, Markets, Marvin Jordan, Mike Pepi, panopticon, platforms, political geography, Politics, post-internet, state, surveillance, the stack

From planetary scale computation to the limits of cloud-based sovereignty, Benjamin Bratton talks to about his current research.

Machine Vision

In his forthcoming book, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, Benjamin Bratton deepens his investigation into the fundamental problems facing design today: obstacles presented by planetary scale computation, or a software-hardware monolith that he calls “the stack”, comprised of “so many different genres of machines, spinning out on their own…” This new schema or “accidental megastructure” foreshadows a disciplinary frontier that forms a core feature of Bratton’s research: the political geography of cloud computing. Data Issue editors Mike Pepi and Marvin Jordan interviewed Benjamin Bratton over email, discussing various conceptions and misconceptions of “the digital”, the limits of cloud-based sovereignty and territory, and contemporary art.

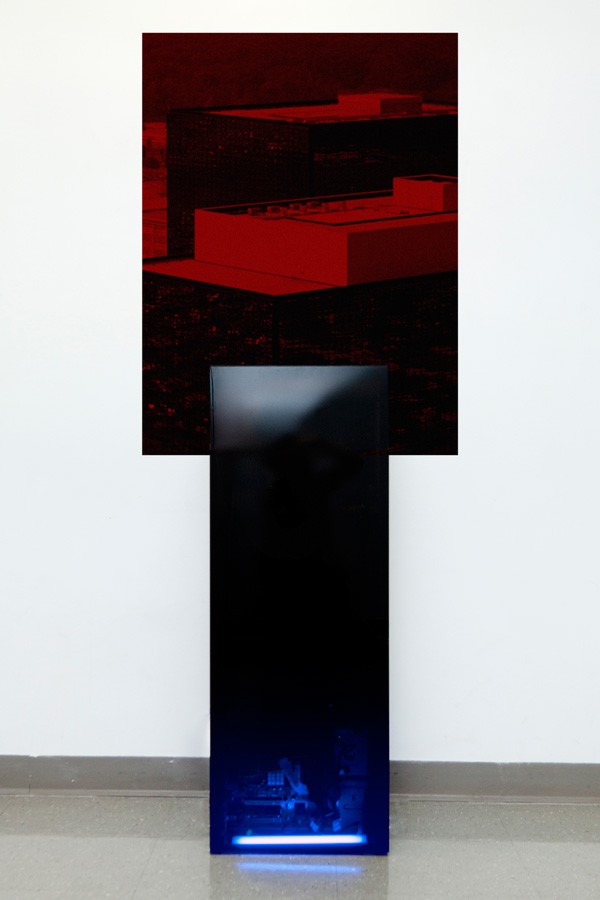

Zach Krall, Inside Cyber Command, 2014

Could we start with the metaphor of “digital space”? There are some who use it as a facile reference to networked capitalism or fictitious “worlds” conveniently placed beyond considerations of class, race, or gender. Yet you’ve discussed the potential of “digital space” in another way, namely, you’ve considered the possibility of ubiquity of “network time” or a world flattened by digital images that map a cosmogram (after Virilio), or Craig Hogan’s theory that the fabric of space is digital (binary) and your theory of the black stack points to the complexities of jurisdiction suggested by planetary scale (digital) computing. How do we chart this conceptual metaphor from acceptable use to abuse? Simply put, how do we responsibly define “the digital”?

Benjamin Bratton: I think the most common abuses of the concept “the digital” are those that start from an idea that computation and algorithmic reason are recent inventions and that their geologic profile amounts to spreading some artificial glassy film over the surfaces of analog nature. This is the basis of a still persistent ‘virtual is to physical as digital is to analog’ misconception. I would argue that humans discovered “computation” more than we invented it, and have as yet built only weak little appliances for harnessing it. Unfortunately, I don’t think there is no single definition of “the digital” that would untangle the popular confusion of computation-as-such with today’s computing technologies or computing culture.

In Art, the digital/ analog division become a Culture War, with bizarre patriotisms on both sides, each developing parallel theoretical discourses, conference circuits, journals, relations with or hostilities toward other disciplines within the academy, etc. There was real cultural capital at stake for the cultivation and weaponization of both Analog Pastoralism and Digital Millenarianism and/or Successionism. It would seem that an earlier generation of curators and gallerists were as befuddled by “New Media Art” as the record industry was by MP3’s and could not figure out how to monetize something that was by definition not a scarce object or gesture. All this is well known, but it does seem to be far less the case than it was. It’s probably too early to say which side really won. Perhaps one won Art and the other won everything else?

When comparing the current stack to the impending “Black Stack”, you place considerable emphasis on a kind of historical necessity underpinning the latter’s relation to the former, going so far as to call the Black Stack “the computational totality-to-come” that is defined by “its dire inevitability”, and which amounts to “an escape from the present.” I can’t help but get a sense of determinism when reading these lines. What makes you so sure that the stack-to-come isn’t already here, or that it will be any different than the current stack’s capabilities?

BB: Understanding The Stack as a model of and for “totality” should not be confused with immutability or even with a closed-system. What is determined is that The Stack-we-have is not historically or technological inevitable and that the modular structural logic of stack architectures makes the displacement and replacement of whatever occupies a given layer if not inevitable then at least foreseeable. The “Black Stack” is simply a name for the “not-blank slate” of whatever composition The Stack will turn into. It is a composition that we know is coming, know that we will have a hand in fashioning, but don’t know how to recognize in advance (or cannot possibly recognize in advance because we cannot possibly ever witness it for whatever reason.) Some ante-verberations of “this-totality-to-come” are surely already here and now. In the Conclusion chapter of The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (published later this year by MIT Press), I outline some current, apparent dispositions of each layer of The Stack-we-have (Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface, User) and suggest possible developments, some optimistic and not at all.

Perhaps your question suggests some discomfort with the not entirely “critical” posture of this Black Stack figure? The book describes itself as a “design brief”. If it lives up to that, it would motivate not just more analysis and critique but projects of designation, making and programming that are, I would hope, better-tuned to the opportunities at hand. I recognize that some readers may be possessed by a philosophical spirit of “infinite refusal”, especially with regards to global-scale technologies, but hopefully they will also find some good ideas and projects to engage with. I would hope that technical and theoretical practice and pedagogy can combine more effectively.

On that point, it should not be so hard to recognize that perpetual spontaneous negation of power is simply not a good master strategy to effect durable accumulative transformation in material power relations (for example) and that a future worth winning needs a Futurism worthy of the name. Perhaps some people have other goals for which that master strategy actually suits them quite well? If so, fine. But it still obscures the fact that it is by the large-scale imposition of fixed, generic protocols of inclusion and interaction, such as the city, that any platform is able to sustain the weird, richly nuanced divisions of labor and life that allow people to pursue the joys of their most marginal idiosyncrasies. This is only paradoxical if you begin with an axiomatic negation of power and form, real or imagined. In other words, “Governmentality” is a technology for the care of the social; it is not an obscenity.

That reminds me of what Natalie Kane wrote recently, inspired by Transmediale, but easily applied to other examples of this type of inquiry. She lamented the loose invocation of “algorithms”, namely that some perpetuated the “idea that we don’t know what they do, we can’t control them, and that they go on to invent themselves like an ever replicating organism”, which “removes the humans that created them entirely.” It seems like the marriage of leftist jargon and theories of and for digital technology have actually increased in a memelike nature as these intellectual communities coalesce, echo, and build off one another online. Meanwhile some have called for a more technically-specific research on these questions, something perhaps viewed unkindly by theorists who would then need to trade in their Jameson for Python.

BB: I would definitely read “Jameson for Python” but I would be more interested in “Python for Jameson.” The Jamesonian reading of high-level general purpose scripting languages is good, the Jamesonian plan and program for what to make with Python is better.

Zach Krall, Inside Cyber Command, 2014

Turning to art, ”Post-internet” is another overextended term that now appears to have been a poorly-conceived set of loose principles. After having a brief rise, those ideas about art seem to be in various stages of backlash or re-organization. In one sense, post-internet work increasingly appears as an art of user subjectification.

BB: An art of/on/for user subjectifcation would actually be quite interesting if it were to take its own provocations seriously. The problem with much Post-Internet Art, perhaps, is that for varying reasons it seems obligated to not complicate its effects nearly enough. To start, it’s not possible to make sturdy generalizations about the quite different artistic practices that get categorized by this term. For example, both Artie Vierkant and Zach Blas were students in Art programs where I have taught, and it would not occur to me to say that their goals or programs are of a kind.

With that caveat, it might, however, be worth first exorcizing what we think we see when we look at Post-Internet Art (which is so clearly about being looked at). One may think that one sees something like a sociopathic Pokemon-inspired smirking in-joke easily downloadable for the Koonsian after-party, one that leveraged an uncertain ratio of ketamine and juice-boxes to circumvent Clare Bishop’s “Digital Divide” by acceding to the White Cube economy’s most transactional 2D wall-friendly file formats. One may think that one sees the inevitable reaction to transposing museum holdings into Big Data image archives in the preeminence of .JPG as a universal visual culture protocol, now extruded and fabricated twelve feet tall for shits and giggles. But maybe that’s not all there is.

First, the user as ocular subject is what a lot of this art either problematizes or resists problematizing. In deciding between the two, it is important to insist that is not really post-internet art. It is, as others have said, more accurately art of WWW, social media profiles, banner ads, MMOG, and stock photography psychodramas, etc. It is about what the web looks like on screens for people who look at screens, as well as the figural contradictions of a screen-based aesthetic that is staged in relation to screens that are at once in and on our physical world. Yes, “hyperreality” and all that, but also making the optical physics and cognitive science of clickbait into an anthropological scenario requiring mimetic reflection. Good, but that is still not the Internet. The Internet is mostly logistical & scan-search morlock algos keeping things running for the binocular-visioned hominids aboveground who look at images on screens.

One of the chapters in the book I am writing now is on machine vision. Depending on how you count, weigh or measure them, there are already far more “images” made by machines and for machines than by humans and for humans. Machine vision is arguably the ascendant ‘ocular user subject’, not the human. At the very least, the human visual subject—especially that user subject construed for mainstream social media—should be situated adjacent to machinic user subjects, instead of above them or before them. This is not part of some OOO wordgame maneuver but a simple fact.

Given that, who/what is the user/viewer of the Post-Internet Art’s combined ‘.JPG-Object‘ format? On the one hand, the oscillation between image-as-object and object-as-image is a way to mimic the movement between virtual and physical screen spaces, and so could be seen as a return to conceptual and perceptual importance by certain Modern “techniques of the observer” that we thought were already well into retirement.

On the other hand, one may conclude that in the conflation of social media screen aesthetics with “the Internet” as a whole, Post-Internet Art feeds on a conservative art world’s validation of collective technical ignorance about the actual workings of an occluded infrastructure—and so guaranteeing its appeal for certain curators and collectors for whom the occlusion of morlocks is core to their business model or personal psychological make-up. This may also easily include the collaborative alibi offered by the individual artist’s claim that the work’s re-performance of that occlusion constitutes a “critique of capitalism,” which is all the better for everyone.

On the other other hand (there is always a third hand), perhaps even while Post-Internet’s observer may impersonate a stupid postmodern blank stare, couldn’t it also be read instead as a pantomime of the machinic visual subject with whom we already co-inhabit the wider subject position the user? Maybe, maybe not. For example, Blas’ anti-facial recognition masks —which I think are great— may be understood as a gesture of refusal to engage with machinic visual subjects, maintaining the human privilege to remain unrecognized by the subaltern machine’s gaze. Or instead it may be taken as a way of exploring how that machine does see, who we are through its “eyes”, and how its gaze can be a site of reflection (literally and conceptually) for the recomposition of our own vision in relation to theirs. Clearly the latter is the more interesting project (and not the only one to derive from Blas’ work). The limited range—from dumb stare to “refusing the panopticon”—is a bad spectrum on which to be stuck, and I wouldn’t wish it on these practices. If they choose to adhere to it, however, that’s their problem.

Could you say more about machine vision?

BB: Yes, I am fascinated right now by its abilities and limitations. I suppose my line of thought would contradict somewhat Bruce Sterling’s essay on The New Aesthetic in which he takes time to dissuade us from reading too much machine intelligence into what we see as an emergent aesthetic pattern. He says that the machines that have produced these images do not and cannot have a sense of “aesthetics” and this is certainly true so far as it goes. He recently made a similar point about A.I. in an interview. Now, it’s true that one can also suppose that allegory, inference and emotion are things that humans do not understand well enough to render algorithmically. Perhaps it’s not the machine’s fault. (Remember Turing’s line from the “Computing Intelligence” essay in which he wonders if a sonnet written by a computer would be best appreciated by another computer?)

However, what I mean by the machinic visual subject is not something that possesses humanlike or human-level perceptual and aesthetic capacities, but rather something that is uncanny and interesting because it does not possess those things and yet can see us, recognize us and know us regardless. That’s weird and interesting enough. It’s also not true that image processing cannot see “genre” (as Lev Manovich’s recent work shows) but it sees it differently precisely because it cannot have any real emotional connection to it.

For now what is sufficiently interesting about New Aesthetic and related kinds of machine aesthetics, as they exist and proliferate in the world, and perhaps about post-internet art as it is simulated within the gallery, is that they (can) stage a encounter with our own estranged reflections. There is the question of how the world looks as a screen, and another, more important I think, is how we look as objects of perception from the position of the machines with which we co-occupy that world.

Seeing ourselves through the “eyes” of this machinic Other who does not and cannot have an affective sense of aesthetics is a kind of disenchantment. We are just stuff in the world for “distributed machine cognition” to look at and to make sense of. Our own sapience is real and unique, but as we are things-to-observe-that-just-happen-to be-sapient, this doesn’t really matter to machine vision. This disenchantment is more than just like hearing the recorded sound of your own voice (“that’s not me”) it is potentially the clearing away of a closely guarded illusion. This uncomfortable recognition in the machine’s mirror is a kind of “reverse uncanny valley.” Instead being creeped out at how slightly inhuman the creature in the image appears, we are creeped out at how un-human we ourselves look through the creature’s eyes. This is something to continue to research further, but in and out of “art”.

Zach Krall, Inside Cyber Command, 2014

Whenever we come across critical or politicized art today that sets itself the task of confronting systems of surveillance or “the digital panopticon”, we’re typically greeted by an old tradition of “demystification.” That is, the assumption that there is a “hidden” agent — be it capital, algorithms, the NSA, etc. — which “secretly” harbors the “real” cause of social oppression. The goal then becomes to “expose the truth”, which will presumably produce a critical epiphany in the heart of the public, leading to righteous social action. Do you see any shortcomings to this theoretical tendency of “pulling back the curtain” from one’s eyes, so to speak — and if so, what alternative methods would you offer for analyzing platform surveillance?

BB: Yes, definitely, but first let me say that it is clear the abuse of power made possible by global surveillance capabilities is not theoretical, it is plainly very real and poses a real danger to retard the full development of the societies and the technologies it purports to protect. Encryption technology will have a big role to play, for good and bad. But, as I have written, the geopolitics of the “User” simply cannot scale from the atomic individual’s counter-weaponization of personal data flows. The fixation on this as both means and ends can also retard the full development of those same societies and technologies.

As for Political Art and Design, there are important differences between types of projects working on this issues, but in general the “forensic” seeks to disclose, reveal, bear witness to a hidden evil and then present them before some ‘public’, whose scrutiny of the illuminated scandal allows them to adjudicate it. The principle is that by revealing and seeing all the bad and serving it up to an authority who can sort it and judge it and punish it, then the work of sovereign justice is done.

One problem is that this spectacle of truth is based on principles similar if not the same as those of systemic panopticism itself, which seeks to automate that disclosure, revelation and administrative accounting of evil/badness. Panopticism is also a forensic impulse, albeit one for which the revelation is itself not revealed. ‘Critical’ works that are content to pull back the curtain and demonstrate before a public the truth of surveillance mechanisms, demonstrating it, bearing-witness and staging encounters are, in some ways, not so much challenging the principle epistemology of panopticism than they are fetishizing it, repeating it in miniature. In the context of politicized digital art, the forensic project can also be a variation on what Wendy Chun calls ‘code fetish’: if we can get to the source and to the source code, and make it viewable, then all the complex social, cultural, economic ramifications and reverberations will be held to account.

There are important and reasonable voices evangelizing the wide-adoption of encryption tools and the protection of Turing-completeness of our personal computers, and I make use of their ideas in The Stack. Others argue for radical transparency and “sousveillance” (as opposed to “surveillance”), but agreement is impossible on who or what is “over” or “under” at any given moment, and so also impossible on who or what should be absolutely transparent and what should be absolutely opaque. Furthermore, the absence of a theory of social form and architecture in this context, without which over and under is so hard to map, is itself perhaps also the result of an automatic impulse to negate, refuse or deterritorialize systems of mutual governance and to disqualify deliberate and explicit prescriptive norms that possess enforceable authority. For the anarcho-libertarian impulse, “power” is always-already a scandal requiring vigilance. Counter-weaponization against governance —by data encryption, guns, encrypted 3D printable guns, etc.—is both ends and a means in its own right. Full stop. This impulse has influenced too much of the discussion, I believe. It’s time to bring more tools to the mix.

Alternatives must start with an understanding that there is not one “Panopticon” but multiple platforms and interfacial regimes competing for line-of-sight advantages over one another. Some technologies of panoptic information are public-facing and largely out in the open, while others hide their existence, and each provides a different but “compete” view of the world. Others are proprietary to financial and military Users. For State vs. State cyberwarfare that competition for line of sight is sometimes even below the level of software, “closer to the metal”, into the hardware itself.

Each platform fights over the ability to identify the “shape of the space” they are fighting over in the first place, which I call the geoscape. Some regimes are State-based and others are non-State based, but for both “governmentality” evolves in relation to what it can see, and the advent of planetary-scale computing allows governance (not just governments) to see and extract value from new flows, namely data. That in itself is not unexpected. It’s simply not possible to understand this overlapping of multiple “panoptic” platforms through a zero-sum heuristic of States and Platforms vs. the Individual. Structural disparities of power in relation to information regimes are structural and need to be addressed as such, not one encrypted individual at a time (even as encryption is itself infrastructural).

Obviously the European and American contexts have different political cultures, and in the USA, the paranoid style is persistent and reactionary, but it is not exclusive to the Right. I once had to correct a student of mine who got very upset during a lecture in which I explained the history of NASA’s Earth Monitoring satellite system. He thought NASA and NSA were the same agency and that the secret police had no business monitoring us with satellites (before I corrected him, he went on to claim that Snowden proved that Climate Change is a hoax perpetuated by elites). He was a smart person, actually, but deeply confused. Clearly for him, and for many others, the very premise of governance observing and tracing events, which is a normal precondition of enforcement, has become itself so illegitimate that it is possible for him to imagine its wholesale refusal as having no costs. His sense of powerlessness about the weirdness of the world is directed at all forms of governance rolled into one omniscient entity. Another student in the same class wrote a paper about the lack of useful reliable environmental data in poor and under-served communities, and the need for more consistent, usable and up-to-date monitoring and reporting systems in those areas. To me, a critical conundrum about the legitimacy of algorithmic governance is made clear. On the one hand, the disadvantaged are themselves rendered into governable data-objects but do not have sufficient facility with media of algorithmic governance, and on the other, the structural violence of living in “Lo-Res” neighborhoods perpetuates the gross inequity by making certain lived realities invisible that need to be seen and need to count.

Back to The Stack and your own work, generally speaking, you categorically demarcate the state, the market and the cloud platform from one another, while obviously recognizing how each interfaces with the others in interwoven ways. Specifically, you write that the “Cloud Polis [i.e., platforms] draws revenue from the cognitive capital of its Users, who trade attention and microeconomic compliance in exchange for global infrastructural services…” To what extent is this “Cloud Polis” really not just a corporation — Google, Facebook, etc. — and platforms are not just markets, new and improved? Don’t these platforms require a certain background of governmental policy in order for them to thrive — as it is with markets? From research and development initiatives to neoliberal legislation, isn’t the state the prime enabler of the cloud polis?

BB: I make a typological distinction between States, Markets and Platforms as institutional and technical forms. I argue that each can and does build on the other but also constructs its own territory in historically and procedurally specific ways. This includes how each of these draws individual actors into their dramas. States have citizens, Markets have homo economicus, and Platforms have users. Sometimes these interpolations align and sometimes they are at odds. When they are at odds that friction can engender accidental forms of provisional sovereignty.

For example, as far as The Stack infrastructure is concerned any agent that can initiate a “column” up and down its layers is a “user” —animal, vegetable, or mineral— and so is in principle just as sovereign as any other user. The potential for a radically agnostic technical-political subject implied by this may also, in practice, undermine how a State segregates citizen from non-citizen and how Markets segregate producers from non-producers. The operative word is “may”. This potential is not a program. The point is not that Platforms are intrinsically better or more egalitarian, rather that their politics are not reducible to those of States and Markets and the terms of our participation requires a different geopolitical design imaginary. The sooner we take them seriously and stop trying to interpret them as quasi-States or quasi-Markets the sooner that design imaginary can mature.

In the book, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, I outline how planetary-scale computation foregrounds the geographic and political logics of platforms and discuss in some detail how some Cloud Platforms (such as Google or Apple) come to take on many of the traditional functions and services of modern states. Given the contemporary preeminence of Platforms as institutional and technical forms, this is not unexpected. At the same time, I also show how States are evolving in relation to what planetary-scale computation allows them to see. States are evolving into Cloud Platforms just as Cloud Platforms come to take on traditional functions of States. These are not contradictory developments, but in practice they do are quite often clash over which mode of sovereign geography and interaction has final priority over which, and for whom.

As for the extractive logic of Platforms that you mention, I argue that this is a generic principle of Platform logics, whether they are State-based Cloud platforms, or Google, or what have you. Platforms do not usually have constitutions and enumerated rights, nor do they usually charge for individual transactions. Participation is more elective, at least in principle, and they sustain themselves by the self-reinforcing logics of network effects, generative entrenchment, and monetizing the optimization of point-to-point information flows.

Users derive value from their participation and from their use of low-marginal cost infrastructure, but in the long run, the aggregate value that the Platform derives from the coordination of interactions is greater. We can easily observe that Platform logics are transforming corporations in their own image at least as much as the other way around. While this political economy of Platforms is clearly compatible with the contemporary corporate entity, it is also compatible with many other kinds organizational strategies that we have not invented yet.

So to your specific question about the enabling promiscuities of State, Market and Platforms: yes, that is quite so. At the same time, however, I will repeat that Platforms are not reducible to States and Markets, nor vice versa, and yet the key geopolitical intrigue of the coming decades is how each formulates the structures of global society with and in spite of the institutional mechanics of the other. As for the central command of Neoliberalism in this unfolding, things are not so cut and dry. Don’t forget that the largest Internet market in the world is China’s. That is where State Cloud Platforms may be most starkly drawn, but to characterize their development as essentially “Neoliberal” would be a mistake. The term would have no specific meaning outside of “big new fast things done with money and computers.”

Your writing on the stack is directed towards a problem of geopolitics – i.e., what happens to sovereignty when it extends to developments unaccounted for in Westphalian modes of political geography. You say that these are the “design problems for the next century.” But I also wonder if this predicament is applicable to a fundamental remodeling of certain aesthetic disciplines, or, if you will, the very “iconologies” that would inform visual art in the near future. How might artistic practices become implicated in the stack-to-come?

BB: The short answer is that art’s capacity to materialize abstraction (and literature’s, and cinema’s) should make it a core and indispensable sub-discipline of Geoengineering, which should itself be a core sub-discipline of Geopolitical Philosophy, which should itself be a core sub-discipline of a combined Synthetic Astrobiology and Computer Science.

Benjamin H Bratton is a theorist whose work spans philosophy, art and design. He is associate professor of visual arts and director of the Center for Design and Geopolitics at the University of California, San Diego. His book The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, is forthcoming. See www.bratton.info and on twitter @bratton