The Invisible Giant: Postmodernism Redux, Part 1| Domenick Ammirati

Keywords: A Cyborg Manifesto, Artists Space, domenick ammirati, Donna Haraway, Frank Stella, gregory crewdson, hal foster, koons, peter halley, ross bleckner, Semiotext(e)

How the art world became a PR enterprise

Part 1

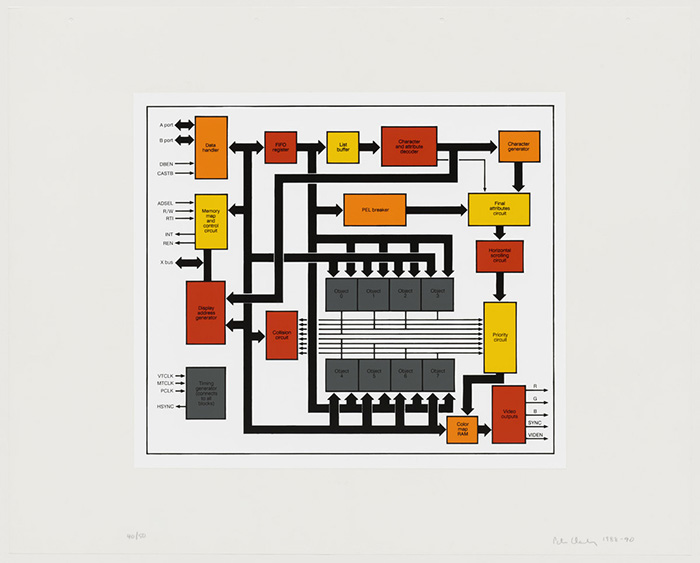

Peter Halley, Accretive Cognition, 2010. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York. © Peter Halley.

In a juxtaposition of types that seems unimaginable today, Penny Arcade was once seated across from Jean Baudrillard at a Semiotext(e) dinner—or so she related at a discussion of the pioneering press at New York’s Artists Space last year. It’s the kind of pairing a host might want to set up to seem audacious, or in hopes of generating a piquant anecdote or two; but even in the event that said host possessed a Lotringeresque diversity of social circles, when the rubber hit the road, our mandarin polity would put on the brakes. Precisely to prevent the sort of thing that occurred.

“You know,” Arcade said, leaning across to Baudrillard, “I thought I hated you. But I realize now I just hate the people who are into you.”

“Me too,” he replied, nibbling at his steak. Or so the story went.

What one might call the “high postmodernist” period of artmaking runs roughly from the early 1980s through the early/mid-1990s. With specific reference to New York—probably its signal site—responsibility for its seeding may well lay with Lotringer, Semiotext(e)’s mind-boggling catalogue, and the 1975 Schizoculture Conference at Columbia University organized by the collective behind the press. An art lineage per se might start with the East Village scene; early tent poles include the Peter Halley–curated “Science Fiction” at John Weber Gallery in 1983 and the 1986 Sonnabend show of Ashley Bickerton, Halley, Jeff Koons, and Meyer Vaisman that brought these artists to a new level of attention. Toward the other end of the span you have Jeffrey Deitch’s 1992 “Post Human” DESTE Foundation show, showcasing Bickerton, Koons, and Vaisman as well as Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Mike Kelley, Kiki Smith, Janine Antoni, and Robert Gober, all in the hands of a major collector; the 1993 Whitney Biennial, aka “the identity politics biennial”; and the Whitney’s 1994 show “Black Male.” The textbook take on what might unify such a divergent array of forms and practices is a desire to interrogate and overturn the master narratives of traditional hegemonic institutions—the state and society, regimes of gender and sexuality, the academy, the art institution. An arguable throughline between artists as different as Koons and Gonzalez-Torres is the sense that the constructs of identity, the templates for personhood that the old institutions had validated and that had served since the Enlightenment (or industrial modernity) were no longer useful and breaking down.

Today, in 2015, a wave of artists are returning to the concerns of the art of the high postmodernist period—questions of image and reality; the coexistence of the human with creations of its own that seem disturbingly independent or quasi animate; the ability of the human to survive increasingly pernicious aspects of spectacle culture and the spectacle’s flip side, surveillance; and the pernicious infiltration of commerce into all aspects of life. The appearance in 2013 of Peter Halley’s Selected Essays, 1981–2001 would thus have seemed timely. The writings of Halley’s wunderkind era through his ascent and apogee in the early 1990s were signature documents of the period. Halley was among the hottest of young things during New York’s Wolf of Wall Street/American Psycho art boom, making flat, affectless, Day-Glo, emblem-like, pseudo-diagrammatic paintings that exemplified his intellectual program. Beginning in the 1970s and cresting through the 1980s, philosophy, sociology, and critical theory by a variety of writers, many French, famously caught on in the American academy, and Halley’s writings, published in Arts magazine and other venues, played a key role in bringing poststructuralism and the rest of what was dubbed “French theory” to the burgeoning contemporary-art scene.1

Halley’s texts on art and culture offer a smattering of the period’s major sources and hot topics in art and intellectual circles.2 In 1987’s “Notes on Abstraction,” he begins with Paul Virilio, cites Barthes and Debord, and quotes from Venturi/Brown/Izenour’s pomo bible Learning from Las Vegas (originally published in 1972, published in an expanded edition in 1977). “The Frozen Land” (1984) addresses the denial of death in an image-based culture—very Baudrillard. “Frank Stella . . . and the Simulacrum” (1986): you get the gist. To what end is this intellectual firepower turned? A number of points that may seem familiar from art circa 2015.

Perhaps Halley’s number one project is to assay of the effects of technology. But Halley’s modus is entirely different, reliant on now-classic (or crusty) theory. In “Beat, Minimalism, New Wave, and Robert Smithson,” from 1981, he boldly links the three enumerated movements via a blunt thesis: “All three express America’s fascination-repulsion for its shallow cultural roots and its vulnerability to the impact of technological change” (“New Wave” here designates a late ’70s/early ’80s group of artists, with Halley’s roster of them—Jimmy deSana, Peter Fend—diffusely sharing interests in technology and media). In “Ross Bleckner: Painting at the End of History,” from that same year, Halley follows Bleckner himself in linking ’60s Op to the military-industrial complex, and cites Bleckner’s appropriation of Op as representing an uneasy resignation with regard to technology and its threats. With a resurgent Cold War and waxing anxiety about Mutually Assured Destruction during this period—Threads, The Day After—nuclear arms served as a common symbol of the negative or even catastrophic consequences of technological development, and Halley uses the nuclear as the synecdoche of our double-edged technological prowess.

Jimmy DeSana, Party Picks, 1981. Courtesy Salon 94, New York.

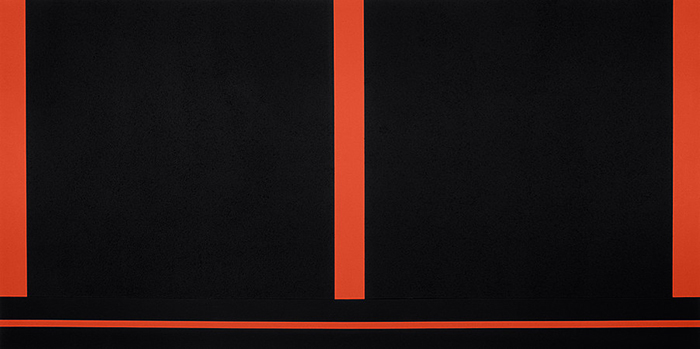

Ross Bleckner, Untitled, 1981.

This is interesting stuff. Replace nuclear catastrophe with the perils of the anthropocene, heavy on the environmental despoliation angle, and you can find numerous artists and writers working in parallel to the terms Halley stakes out. Why, then, did the Selected Essays, issued by the tiny Edgewise Press, receive little notice and pretty much zero critical interest? Why today does much of Halley’s writing seem corny and old?

There are of course key differences between Halley’s heyday and the present in the intellectual climate around art. Consider, first, the label “French theory.” It has an odd ring today—emphasis on “French.” Writers lumped together in the ’80s— Baudrillard, Derrida, Foucault, Irigaray, Kristeva, Lyotard—were decidedly imported. The appearance in art discourse of those thinkers at that historical juncture had much to do with the resurgence of American triumphalism, after the election of Ronald Reagan and improvement in the economy, as the Soviet Union began to show signs of crumbling. (Gorbachev took power in 1985, the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.) Halley and others could thus position themselves as critiquing American culture and American values as they took on the role—like the market—of the only game in town. Recovered from ’70s malaise and ascendant (the period’s paranoia about Japan notwithstanding), the United States was a global colossus, identified with technology but also with artifice and image making—Hollywood, the entertainment industry. The sitting president, as loathed in art and the academy as he was beloved generally, was viewed as a figment and symbol of the new regime of images we had entered. Cable TV may not seem like much now, but at the time it was spoken about in language very similar to the way we talk about the internet today—the loss of attention span, the seductiveness of disappearing into an image world, the corrosive omnipresence of entertainment, the niching of content per consumer group.

Halley’s writings of the time are preoccupied with America. In “Notes on Abstraction,” a text interpolating sometimes-lengthy quotes, the preponderant subject is American iconography: Hell’s Angels and Hiroshima, an airline call center in San Diego, a theme restaurant, the mall, Howard Hughes, the Las Vegas casino, a Kohler ad for plumbing. And in fact the oldest source, from 19th-century France, is about the Palais Royal, Paris’s first covered shopping arcade—i.e., a paleo-mall. Elsewhere it’s Coca-Cola, the Cadillac tailfin, Walt Disney on ice. It’s not to say these references are inapt, but they are so iconic that in 2015 it’s hard to tell whether Halley chose them because they were hackneyed, whether they had not yet become hackneyed, or whether it’s just bad writing.

Today such U.S.-first concerns, so recently urgent, seem antique. As the United States has tapered its military adventurism, art discourse has become generally uninterested in America, or even the United States, which we became more recently, when we fell to earth post-9/11 and post-crash, moving from being a locus of dream to a pedestrian and crumbling nation-state. The U.S. is no longer a stage set, a plywood town in a Hollywood western, a false front with corruption simmering behind its smiling mask, that classic theme of art from the American century (from Elmer Gantry to, say, Gregory Crewdson). The rot has visibly eaten through the skin. Concomitantly, the sense that America can be redeemed or recovered, which was implicit in those critical (and ultimately nostalgic) takes of Halley’s writing and contemporary artwork, like that of, for example, Koons, has evaporated. Moreover the idea of a nation-state itself is less central than it used to be, as it’s become abundantly clear that ties or slices across national boundaries are superceding more “vertical” assemblies. Contemporary art as we know it is an artifact of global economic stratification, so it is unsurprising that its foci are highly internationalized and that the now-provincial issues like those related to Americanness are passé, or in some sense déclassé.

A more subtle distinction between the then and the now lies in the province of attitude. The theoretical hot stuff of the 1980s was notably attacked for its negative outlook, and not just by mere reactionaries. (“Postmodern irony”—remember that chestnut?) No less a personage than Hal Foster, for example, in his 1986 opus on the painting of the day, “Signs Taken for Wonders,” derided Halley et al. for being “nihilistic.” This bad attitude might seem a point of greater alignment with the art of today, since the “nihilism” for which postmodernism was attacked has only come back stronger, if it ever abated. In the 1980s sources of nihilism in art and its interpretations might have lain in causes such as, for example, the acknowledgment of the loss of autonomy for art from “the world”; or the perception that culture had been debased to the degree that one could no longer tell the authentic—and hence good—from the ersatz, the image from the referent; its more subconscious and more gross, a loss of purchase by “tradition,” aka the old white male order. The New Criterion, lest you imagine it a product of the 1950s, was founded in 1982.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled (Beer Dream), 1998. Courtesy Luhring Augustine Gallery, New York.

Today any dark outlook in art is parallel to the mood in the broader culture rather than opposed to it, and its inspirations seem as grim or grimmer. Beyond imminent planetary death—the latest global-warming tipping-point date is 2047—there are important in-group causes as well. As the twenty-first-century sequel to the ’80s art boom disgorged enormous amounts of cash, it made economic stratification all too clear. Artists have always had problems with the art market (Michelangelo had his problems with the man who cut his checks, the Pope), but it’s become more difficult to cozen oneself into ignoring it and the concerns it brings up, particularly after the professionalization of art, where advanced degrees predominate and prospects for MFAs are as scripted and worried over as those for MBAs or JDs, or our sad cousins, the PhDs. The anxieties, the existential despair, the angst (if we can use that term seriously) of the immediate circumstances are great, and lead easily to cynicism. Then consider the general landscape post-crash, in which the world-economic system has been revealed to be a house of cards, with the 99% to be the ones injured in its occasional collapses.

The anxiety that fueled initial laments about authenticity have, on the other hand, sublimated in the vacuum of a no-longer-new order of image culture. Appropriation as an art tactic isn’t terribly noteworthy anymore. References? You can get them or not, whatever. The Internet so thoroughly deracinates images as well as words and iterability has become so pervasive that a loss of essence and a dependence on context are no longer scary radical fringe. If they rouse anxiety, it’s because we realize they’ve become corporate.

There are some writers, of course, who came to the fore in the ’80s whose writings are also apposite to the present but who enjoy current intellectual prominence. Donna Haraway was a significant figure at 2012’s Documenta, where she was not only an advisor but also exhibited, in a small cabin, a substantial archive of materials related to animals and animal consciousness that seemed to lay the foundation for one strain of the work in the show. The bulk of Haraway’s work has in fact been related to the question of human and the animal; but her still most well-known text is of course aimed at another duality we have traditionally used to construct the human—1985’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” which articulated a new kind of identity born of technological progress, neither human nor machine, genderless, labile, a survivor. Like Halley’s musings, the essay is overhung by the possibility of everything going up in irradiating plumes. The cyborg was, however, not a figure of apocalypse but one that might effect an improvement in our world (“salvation” being a term to avoid in this lexicon). In a climate of often dark theoretical constructs, this explicit optimism was perhaps as significant as any of the number of other aspects that make “A Cyborg Manifesto” continuingly vital.

Janine Antoni, Lick and Lather, 1993-94. Photo: Ben Blackwell. Courtesy SFMOMA, © Janine Antoni.

It’s also true that, better than any of Halley’s applications, the cyborg is a synecdoche for a major corollary of poststructuralism that’s also highly relevant to art today—the idea of posthumanism. In 1966, in The Order of Things, Foucault famously wrote, “Man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end.” His genealogical unravelings of dominant discourses are the lodestone of the effort to move beyond humanism—i.e. to see what comes after the collapse of the Enlightenment intellectual edifices that gave human beings their role at the center of the universe. Hence the crises of identity of the postmodern period. By the 1980s, advances in communications and transportation technologies had begun to clearly imply a new blueprint for the human that lacked core or essence and that was constituted only conditionally, contextually, in fragments. The idea of “human identity” of a single thing was thereby compromised; better to speak of blueprints under infinite revision and reproduction, rather than a single blueprint mimetically executed, for this host of new selves.

Halley is onto the discourse of posthumanism as well, of course, frequently citing or using the motifs of transit, relay, and circulation—the downfalls of fixed identity, meaning, or essence. In his Stella essay, he argues that Stella’s patterning changes from modernism to postmodernism beginning with the Aluminum Paintings: “The introduction of the ‘jog’ suddenly makes the bands appear to be moving: they are like lanes on a highway; they are bands for movement and circulation,” he writes. “Abstract circulation and movement becomes the only reality.” In later works, the movement is “more akin to electricity moving through a microprocessor than mere automobiles traveling on a highway.” For Halley, the key is the boundedness of the circulation, with an emphasis on circ-; circuit, circle, a closed system. This no-offramp quality means that what appears to be movement is its illusion, actually just disguised stasis, no real movement at all. This stasis yields not identity but a simulacrum of identity. This reduction is entirely counter to humanism, but not in any emancipatory form such as that articulated by Haraway. As Halley writes in 1987’s “Notes on Abstraction”: “Marxian thought has always assumed that the breakdown of the pretenses of humanistic culture would yield a reality that was more responsive and coherent than that of humanistic illusionism. Yet behind the mask of humanism there exists not the truths of materialism but … a crystalline world responsive only to numerical imperatives, formal manipulation, and financial control.”

Tue Greenfort, The Worldly House. An Archive Inspired by Donna Haraway`s Writings on Multi-Species Co-Evolution Compiled and Presented by Tue Greenfort. Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA (13). Photos: Nils Klinger. Courtesy Tue Greenfort and Donna Haraway.

Frank Stella, Diepholz II, 1982. Courtesy Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas.

This view of the world is precisely what Halley illustrated in his practice—perhaps too precisely. And it is in so doing where his great contribution to art and art discourse, as well as his cardinal sin, may lie.

Halley’s paintings, with their cells and connecting conduits, appear to be little more than diagrams of his ideas, with the bright, clashing tones evoking the jarring nature of the garish late-capitalist world in which we find ourselves. The works’ highly mechanized, high-volume production threw in a Warholian angle, as if—à la Koons—to pose the very exploitation of the market as a critique of it. With his writing, acting as a populizer rather than a theorist—cf. Haraway—he helped sculpt the consciousness of a newly developing art scene. Emphasis on “scene.” Halley was important to bringing theory to artists, yes, but moreover to the new promotional and commercial class then beginning to take root around them, as well as the self-promotional functions that artists themselves were beginning to more actively take on. It was in the ’80s, with the birth of the contemporary art market, that the press-release, money-wet, catchphrases-and-cocaine culture of art we still inhabit began to take hold. Halley represents the first perfection of press-release art, in which the theory behind the work justifies, or overtakes, the work’s existence. Contrast this set-up with that of its predecessor, Conceptualism, in which the idea is the work, at the movement’s limit in a strict ontological sense. Conceptualism proper is based on a scrutiny of ideas, an unraveling of them and a rooting around in them, while the way in which a conceptual aproach was taken up in the 1980s fosters instead the iterative dissemination of ideas that come preloaded.

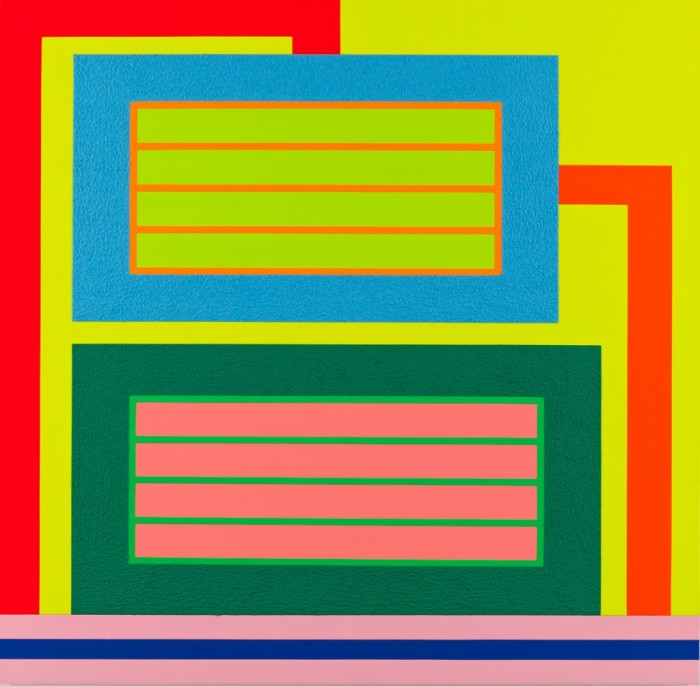

Peter Halley, Two Cells With Conduit, 1987. © 2015 Peter Halley, Courtesy Guggenheim, New York.

The hallmark innovation of the high postmodern period, then, may well have been the creation of a new attitude toward the relationship between ideas and art. Art began to operate under a mandate that art and artists take recourse from “cutting-edge” thought—philosophy, sociology, etc., best of all the newly coalescing in-between realm of critical theory. Up-to-date post-Marxism, sure, that’s fine, but the more novel the better for the fabrication of the intellectual props that became and remain necessary to market one’s art. The same rules apply to critics and curators, the former shuffling toward extinction (at least in their classical form), the latter reciprocally exploded in numbers and highly professionalized—and of course to the new class of gallery personnel. The belletristic ceased to suffice, and theoretical verbiage, good or bad, earned or foolish, is vital to young artists seeking to gain career purchase (outside a certain style-magazine faction that has been most enjoyably, ironically signified by posthumanist manqué Jeffrey Deitch). This conversion of intellectual discourse, the product of the academy, into a commodity matches the shifts that have occurred in the latest iterations of the evolution of capitalism: the Italian philosopher Paolo Virno articulates this seizure of communications and the communicative faculty itself by capital in his A Grammar of the Multitude (2004).

It would be stupid to ascribe responsibility for the current state of affairs to Peter Halley et al., but après them, the deluge, and they inhabit as a result a miasmic cloud of blame, scapegoated for the one aspect of their output that’s most relevant, for starting what we all still do ourselves.

In his essay “Signs Taken for Wonders,” Hal Foster discusses—and largely criticizes—the then-ascendant painting practices of Halley, Bleckner, Levine, Bickerton, Vaisman, and Taaffe. Describing how deconstructive moves become “programmatic,” he writes, “It may be that, for Bickerton and others . . . analysis is now a dead end. Yet . . . it is not clear whether these artists receive this critique as historically reified—as an ‘absurd, pompous, saturated and elaborate system of cul-de-sac meanings’—or whether they seek to render it so. In any case, the operation here is more nihilistic than dialectical.”3 (The interior quote comes from a 1986 exhibition statement by Bickerton for a show at Cable Gallery in New York.) While what Foster calls the “new abstract painting” may indeed not have been wholly, partially, or at all progressive or critical, it was more than merely a moment’s diversion. The work was lastingly important for its shift in frame of intellectual reference, and moreover for that nihilism Foster himself identified—the particular nihilism latent in making a necessity of high-toned intellectual rhetoric to create an agreeability to the market. Foster largely keeps the ’80s market boom that enveloped the subjects of his discussion in “Signs” outside the frame of reference until the end of the essay, where he uses it as a jack-in-the-box closer. He ends by declaring that what looms behind these artists’ works is simply free-market economics: “It is the abstractive processes of capital that erode representation and abstraction alike. And ultimately it may be these processes that are the real subject, and latent referent, of this new abstract painting.”

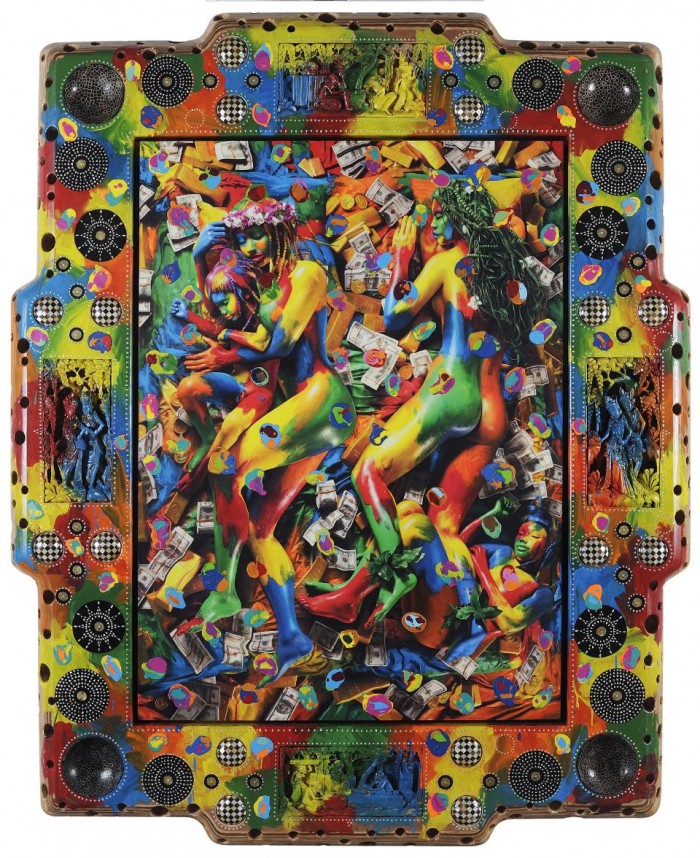

Ashley Bickerton, Bed, 2008.

It seems very likely that Halley would have concurred, but in a manner opposed to Foster’s quiet, clear discontent. In “The Frozen Land,” he writes, “History has been defeated by the determinisms of market and numbers, by the processes of reification and abstraction.” Eschewing just the sort of traditional Frankfurt School response that Foster embodies, he goes on:

Another kind of response is then called for. Ideas that themselves change or dissipate as they are absorbed, that are formed with the presupposition that they will be subject to reification. Only a rear-guard action is possible, of guerrilla ideas that can disappear back into the jungle of thought and re-emerge in other disguises, of fantastic, eccentric ideas that seem innocuous and are so admitted, unnoticed by the media-mechanism, of doubtful ideas that are not invested in their own truth and are thus not damaged when they are manipulated, or of nihilistic ideas that are dismissed for being too depressing.

An important strain of art and critical writing has recently swerved in just such a direction: reproduce the logic of the system until it destroys itself in a glorious detonation of feedback; accelerationism, in one guise. It’s appropriate that clear, ardent, and historically punctual articulations of this position lie with Halley, and surprising, from a certain perspective, that he is rarely cited for them.

In another key essay, 1994’s “What’s Neo about the Neo-Avant-Garde?” Foster unspools a complex response to a couple of vexing yet perpetual and deceptively simple queries. Why does art repeat itself in waves? More specifically, “How to tell the difference between a return of an archaic form of art that bolsters conservative tendencies in the present and a return to a lost model of art made in order to displace customary ways of working?” In the end, Foster arrives at the idea that the good, valuable 2.0 of an art movement does not merely comprehend the “original” but rather constitutes or creates its meaning: as with trauma, “One event is only registered through another that recodes it.”4 It is only in the repetition, driven by the unconscious, that the past is apprehended at all.

Foster provides a model for how to answer important corollaries of what we might call the Penny Arcade Question—how do we know who to hate? So: say a deployment of critical theory to create a new kind of “prop art” is among the less apparent, more extensive underpinnings of the vague of the ’80s–’90s that is currently enjoying a reprise. How then do we find that the body art-historic is “recoding”—to use Foster’s timely-avant-la-lettre choice of verb—that union today? The key to answering that question may lie in the answer to another: How did Semiotext(e) get it right but Peter Halley somehow get it wrong?

Domenick Ammirati lives in New York and writes both art criticism and fiction. A recent fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, he is at work on a novel.

1. The essays in French Theory and American Art (Brussels: (SIC); Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), edited by Anaël Lejeune, Olivier Mignon, and Raphaël Pirenne, are a valuable resource for anyone interested in this subject. For this essay in particular, Sylvère Lotringer’s “American Beginnings” (pp. 44–76) and the editors’ introduction (pp. 8–41) provided useful framing.↩

2. All the Halley essays cited are available in the writings section of his website, www.peterhalley.com.↩

3. Hal Foster, “Signs Taken for Wonders,” Art in America 74, no. 6 (June 1986), pp. 80–91, 139.↩

4. Hal Foster, “What’s Neo about the Neo-Avant-Garde,” October 70 (Autumn 1994) p. 30.↩