Boinas and Bérets: A Little History

Keywords: 60s, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Basque country, beret, Black Panthers, Carlist, carlista, che guevara, Discussion, Dizzy Gillespie, eta, Fashion, france, Jean Borotra, militant, Pablo Picasso, patricia yague, radical chic, spain, vasco

The béret is a unique clothing item that represents antagonistic cultures: the war and the arts.

Jean Borotra at the net, French Championship 1924, La Croix Catalan Stadium in Paris

French-Basque tennis player Monsieur Jean Borotra, member of “The Four Musketeers” (including Jacques Brugnon, Henri Cochet, and René Lacoste) would stop in the middle of a game to put on one of his famous black berets (or blue, other sources disagree—then black and white pictures don’t help to clarify). Borotra, a native of the seaside town of Biarritz, reigned on the tennis courts in the late 1920s. He won 15 Grand Slam, Wimbledon in 1924 and 1926, and single titles at the French Championship (1924 and 1931), the Australian Championship (1928), and the United States Championship (1926). His charisma and professional success brought his trademark headwear into the spotlight in Europe and the United States.

Borotra’s hometown is located in Aquitaine, southern France, a region that lies in Basque territory (Spain). Basque flags and emblems adorn the city. Understanding this crisscross of French and Spanish symbols is key in following the winding routes that took the history of la boina, Spanish term for such a hat, or txapela, as they refer to it in the Basque Country.

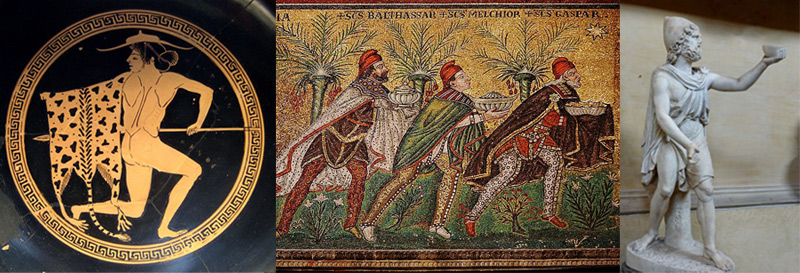

Young boy wearing a Petasos (Greece); Los Tres Reyes Magos (The Three Wise Men) wearing Pileus; Odysseus weaing a Pileus

First off, the beret led us on a trip around Europe; Italy and Denmark during the Bronze Age (3200-600 B.C.) Austria (400BC), Germany (12th Century), France (1280), and Spain (13th Century and so forth)… Archeologists found traces of hats similar to berets in Bronze Age tombs, as well as representations in figurines and sculptures in western and northern Europe. These pieces of headwear differed slightly in size or shape, but there was one characteristic that linked them all: felt.

Felt is the simplest and oldest form of cloth. It’s a non-woven material made from matting and pressing wet fur, generally wool, a material that twines and grips easily due to the inherent nature of the hair. Fate helped humans to discover felt; shepherds used to fill their shoes with wool tufts for commodity and weather protection. Thus, sweat moisture, and walking pressure helped the natural process of creating the felt. Pastors would stumble upon a piece of compact cloth after a long walking journey.

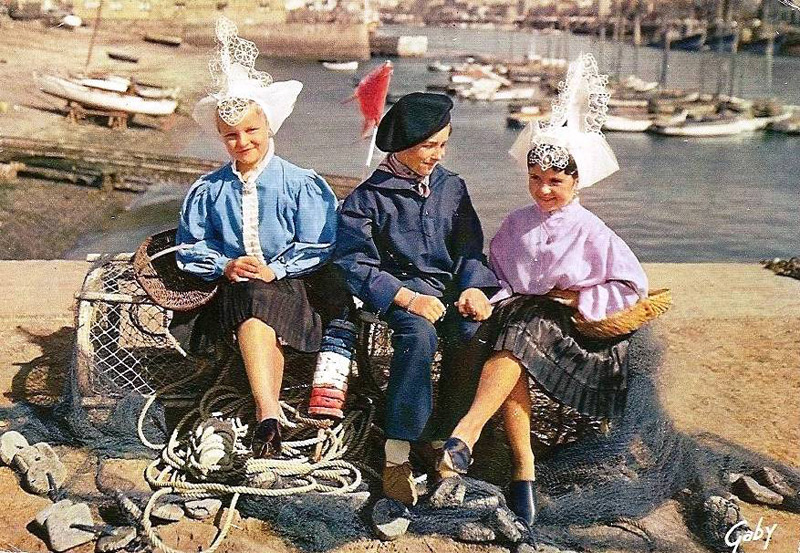

The simplicity of felt’s making process and the quality of the material made it an optimum textile for weather protection. It was commonly used for dwelling, clothing, and head decoration around the globe for many centuries, especially in cold regions such as central and northern Europe. In fact, hats similar to Basque-French berets were worn in European countries such as Italy, Netherlands, and Scotland. However, we find differences among them, most of all the inward shape of the Spanish version and the txertena, a half-inch tail sewn on the top. Another difference to consider is the way the hat was worn: pulled all the way down in northern Europe, loosely placed on top of the head in the Pyrenees counterpart.

In the 15th century, farm workers from the French region of Bearn (southern France) used to wear a type of beret that became very popular among the French Pyrenees population. Then, it jumped to the Basque region of Guipúzcua by way of the French/Spanish Bidasoa River. Since then, la boina became the Basque headwear symbol par excellence.

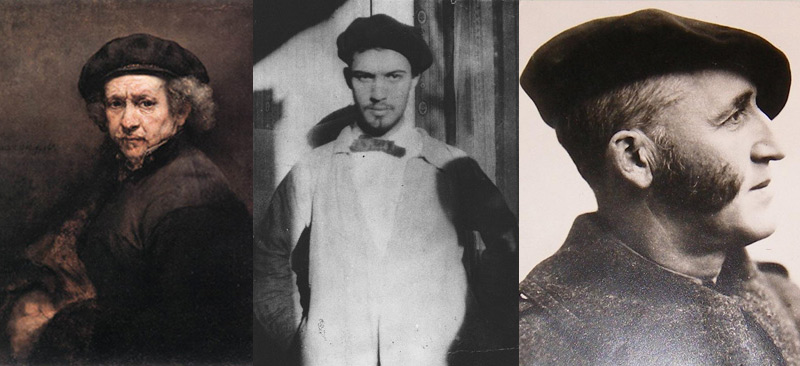

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, 1659; Portuguese Artist Amadeo de Souza Cardoso; Basque Carlist Ignacio Baleztena aka Premín de Iruña

In October 1830, the (soon-to-be) only Spanish female monarch in modern times, Isabella II, was born. Her father, King Fernando VII, aware that his crown “prince” was not going to be male, canceled the Salic Law of 1713 that excluded females from inheriting a throne, months before his daughter was born. But not everyone agreed with his decision. King Fernando VII’s brother, Carlos María Isidro, later Carlos V, successor to the throne of Spain up till then, denied his brother resolution and kept his heir rights. His reaction culminated in the last major European civil war in which opponents fought to establish their right to a throne; the Carlist Wars.

Carlists (defenders of Carlos V) and Cristinos (defenders of Isabella II, called “Cristinos” in reference to Isabella’s mother’s name Maria Cristina) divided Spain. The Basque Country backed Carlos V. The United Kingdom, Portugal, and France helped the Cristinos.

Painting of a Carlist; Tomás de Zumalacárregui y de Imaz; Portrait of a Carlist

During the Second Carlist War (1846 -1849) French txapelgorris, or “red hats”, entered the Basque Country to aid Cristinos in the area. Cristinos started wearing red berets; however, the red berets became a carlist symbol when Zumalacárregui, Basque Carlist general and one of his most important figures, was seen and portrayed with this type of beret.

In the Oscar-winning Spanish movie Belle Epoque (Fernando Trueba, 1992), the Carlist uniform is worn by one of the main characters during a carnival scene, where we can see locals wearing black berets too; it was a peasant symbol. But to add more confusion, we also see it as an emblem of the extreme right when worn in the Carlist manner.

The beret is a distinctive item in military clothing, particularly associated with elite units in nations such as Denmark, Angola, or United States. Therefore, another path crosses our history.

French Army captain with Afghan National Army officer; French Chasseurs Alpins (Infantry)

The ETA's last video message, 2011

The petasos, a floppy sun hat made out of felt (leather and straw were common materials, too) was a ancient Grecian headwear generally used among travellers and peasants, worn by Hermes the messenger god. This headpiece seems to be the direct origin of our beret, although historians keep referring to the pileos, a conical hat used by sailors and the military, as the one. Ancient Romans adopted the pileos, historians say, and changed its name to beretino, thus beret (although here, once again, my skepticism is aroused: I haven’t found enough evidence that such a name was really coined).

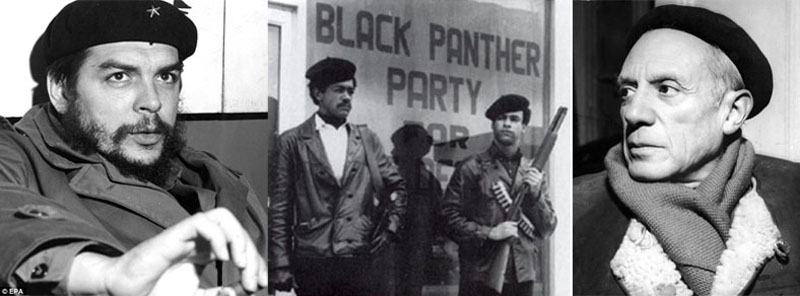

It’s interesting to find a clothing item that represents such antagonistic cultures: the war and the arts. Either artists or the military wear the beret, and both give it their own (and often opposite) connotations. And we understand those connotations too. Jazz trumpet player Dizzy Gillespie wore it often, and so did Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, the Beat generation, French Infantry Commandant Soutiras, mega star Pablo Picasso, existentialist Simone de Beauvoir, and American writer Ernest Hemingway—and many peasants all around the world.

Dizzy Gillespie; John Lennon; Jack Nicholson and Angelica Huston

Che Guevara 1960; Black Panthers 1966; Pablo Picasso