Coffee to Go

Keywords: ally mcbeal, anna lundh, buckminster fuller, coffee, dunkin donuts, fika, jerry seinfeld, kramer, mcdonald's cafe, men in black, nypd blue, seinfeld, starbucks, sweden, swine flu, thermos

The cultural runaway train that is the to-go coffee industry: is it heading for a crash? Anna Lundh investigates what may have been a terrible idea to begin with.

At the risk of sounding like a smug European (disguised as Jerry Seinfeld), I ask this question: What’s the deal with coffee to go?

Not only has this phenomenon been around for quite some time, but it is no longer exclusive to America. Sweden was arguably the first European country to eagerly adopt the take-out coffee habit, while countries like Italy and Spain have been more resistant. The to go coffee cup has become an accessory—seamlessly integrated into our lifestyle—and a more or less obvious ingredient in the make-up of the modern citizen moving around in the public realm. Yet there are signs that suggest something has gone terribly wrong. I was introduced to coffee to go on my first visit to New York in 1998. I stepped out of a deli and into the path of a hurrying man who was taking the first sip of steaming hot coffee. His sudden maneuver made the coffee miss its target. “AAAAWW!” he shouted, “You burned my lip!” I was shocked, but also very confused about who was to blame. Had he not learned not to run with hot liquids? When you think about it, it sounds like a pretty bad idea: transporting scalding hot coffee from one location to another, with risk of burning yourself or spilling it all over the place. Are these to go cups really used as a time efficiency solution, or do they serve another purpose that overpowers common sense?

Already in the second sentence of Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, Buckminster Fuller pointed out a seemingly obvious truth: The best way to design a life preserver is not in the form of a piano top. The point being that even though a piano top can serve as a life preserver (if that’s the best option from what might be floating around in the water at the time of the shipwreck), it should not necessarily be the model for all future life preservers. Seemingly obvious in his example, yes, but Bucky claims that we are clinging to way too many piano tops, and that instead of fixing a problem with the first emergency solution that comes floating by, we should think about things from the largest perspective possible and considering the consequences for the whole Spaceship Earth and its inhabitants, even if that means having to start from scratch or rethink something entirely.

Before coming to New York, my own understanding of American coffee culture was more or less based on what I had seen in sitcoms like Friends and Seinfeld. But these shows had been inconclusive about the true conditions of this matter. In Friends, the “friends” were always meeting at Central Perk, the local coffee shop so closely resembling a typical Swedish cafe where you sit down with a friend for a long “fika.” The people made it seem as though New Yorkers were all about “fika,” and never did you see a to go cup anywhere; the coffee was consumed in large porcelain cups, at the cafe. Just like in Sweden.

Before coming to New York, my own understanding of American coffee culture was more or less based on what I had seen in sitcoms like Friends and Seinfeld. But these shows had been inconclusive about the true conditions of this matter. In Friends, the “friends” were always meeting at Central Perk, the local coffee shop so closely resembling a typical Swedish cafe where you sit down with a friend for a long “fika.” The people made it seem as though New Yorkers were all about “fika,” and never did you see a to go cup anywhere; the coffee was consumed in large porcelain cups, at the cafe. Just like in Sweden.

As long as George and Jerry kept their stable habit of having coffee at Monk’s, the illusion was maintained in Seinfeld as well. The diner culture seemed slightly different than the “fika” culture, but at least they were sitting down. Of course there was Kramer. Kramer, who started drinking Cafe Lattes and claimed to have set the trend back in fifth grade. Kramer, who tried to wear his caffe latte in his pants when sneaking in to the movies and consequently burned himself senseless, thus proving that moving around with hot liquids is not a wise idea (and something only a weirdo like Kramer would do). Right?

Enter Ally McBeal. (Yes, the show became quite popular on Swedish television.) Here came the first clue to what was really going on. Forget cafes and comfy couches, now the hangout spot was a unisex bathroom and the timeframe for small talk reduced to the time it took to wash your hands. Business and busyness does not allow for drinking coffee sitting down, except maybe by your desk. All of a sudden, the disposable coffee cup had become an important symbol of work efficiency as well as power play within the workplace. (Who were to take the coffee orders from whom?)

“You were about to drink this cappuccino the way most men make love, skipping over all the foreplay.” says Ally to Georgia before showing her how to drink the first cappuccino of the morning. This scene not only oversimplified gender roles and sexuality, but also showed that coffee was no longer a reason for social interaction, it was something to do for yourself, by yourself. Here the Starbucks cappuccino cup had become a fetishized object — large, warm and with white foam oozing out of its plastic lid—and consuming it could only be compared to masturbation, preferably with male coworkers secretly looking.

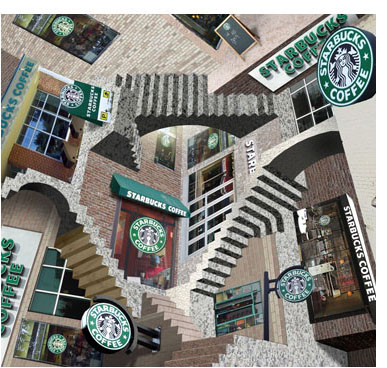

After Starbucks had entered the market, taking the coffee to go could be ruled out as a time-saver, considering the multitude of choices when ordering, not to mention the long lines. Instead the to go cup itself became a symbol of the time-efficient citizen. In the era of wireless network cafes, where we sometimes actually might be sitting down to drink the coffee next to our computers, we still take the coffee in to go cups. Perhaps the cup signals busyness and flexibility, whether it’s used in motion or not?

But Starbucks, which is still spreading like an epidemic all over the world, cannot be held responsible for the to go cup phenomenon, the story is more complicated than that. It started over a century ago thanks to a completely different kind of epidemic:

In 1907, a lawyer in Boston named Lawrence Luellen became interested in creating disposable cups for drinking water. At this time, people drank from water pumps in a communal metal cup, which spread bacteria and disease. Only after many failed attempts with different kinds of cone shapes and with both foldable and expandable models, Luellen found a form that worked: the present-day paper cup. In 1912 he launched his invention, which he called the Health KUP.

Despite extensive campaigns to inform the public about its health benefits, it wasn’t until 1918 that the Health KUP gained popularity, thanks to the Spanish Flu. The disease was first observed in Kansas in March 1918, and shortly thereafter in Queens, New York. A more aggressive version of the flu broke out some months later, both in Boston and in Europe. In November of the same year, 600,000 Americans had died, and subsequently it was no longer difficult to sell the Health KUP. These cups, which would later be named Dixie Cups, were virtually identical to those with which people all over the world are now carrying around coffee. But how did these sanitary water cups turn in to coffee cups?

When Greek immigrants came to New York, they brought their coffee culture with them, opening up countless delis and diners, and in 1963 the paper cup company “Sherry Cup” saw an opportunity to expand its market. Leslie Buck, an employee in the company’s marketing department (himself an immigrant from Czechoslovakia), was given the task of selling the cups to Greek vendors. At first, there was no luck for Mr. Buck. But then he decided to design a cup that would remind the Greeks of their home country, and the blue and white “WE ARE HAPPY TO SERVE YOU” cup was born. The “Anthora,” as he called it, immediately became a huge success, and this mug is still the best-selling paper cup in New York City. Outside of New York the design is relatively unpopular — except with Hollywood set designers, who use the cups in movies and TV shows like “NYPD Blue” and “Men in Black.”

I asked to some NYPD cops about their coffee drinking and donut eating habits, and if drinking from the Anthora cups was required to look like real police? “Yeah, it’s a Manhattan thing, those cups… I drink ‘em all day long, maybe 10 a day,” said one. “We don’t have a big enough paycheck for Starbucks. But honestly, I prefer Dunkin’ Donuts coffee over Starbucks any day. But no donuts for me,” said another and flexed his arm muscles.

Last summer the New York Times published an article called “Cultural Landmarks of a Different Kind,” about tourists’ impressions of New York. “The coffees here are so big. In Spain we drink coffee in little cups, nobody drinks coffee on the street, and you never drink out of plastic,” said Ana Rosa Bermejo from Burgos, Spain. If coffee to go culture has become somewhat of a tourist attraction for some, it has been uncritically adopted by others.

In 2005, two young Swedish designers decided to reproduce the legendary coffee cup patterns Adam (blue dots) and Berså (green leafs) from Gustavsberg (one of Sweden’s oldest and most distinguished ceramics companies) onto McDonald’s paper cups.

“Nowadays people are drinking coffee on the run, so we contacted McDonald’s because they symbolize the modern society,” said Linda Solvang, one of the creators.

“Why not make the world a more beautiful place, by reaching out to as many people as possible with beautiful design?” said Birgitta Hansson, the city culture official who helped finance the project.

This is a perfect example of a very shortsighted way to work with design. Dress something up in pretty nostalgia and have the idea sanctioned by a prestigious ceramics company—of course people will buy it. No challenge there. The only winners here were McDonald’s, who increased the sales with 23 percent on these stylish paper cups. At least they could have chosen to use the profit for some good – aren’t there many causes in real need of a sales boost?

Another example of when the logic has gone haywire is the ridiculous thermos cups, made to please the environmentally conscious. But how practical are these giant things to carry around? They leak, they smell, and they are awfully ugly. I recently saw a thermos cup that was an imitation of a normal paper cup, talk about emergency solution on top of emergency solution!

We need coffee. But how do we need it? That’s a question up for debate. To go back to the communal cup might be a bad idea considering the Swine Flu and other health hazards. We can either continue to invent new emergency solutions to try to repair the damage made by the previous one — OR we can reconsider our behavior and vanity about the coffee cup as an accessory. If we admit that’s what it is, perhaps we can agree that this piano top is sinking.

I’m not saying we have to adopt the long “fika” sessions from Sweden, at least not every day. But perhaps we can give ourselves permission to enjoy our coffee standing still at the bar like the Italians? Are those 5 minutes you would save by walking really worth the cost of all the burn victim law suits, dry cleaning bills and the devastation of our Spaceship Earth? And when you leave the cafe you are liberated. All of a sudden you have an extra hand that is free to wave, free to high five, free to point, free to be put in your pocket, free to hold your hat down when it’s windy, free to hold the door for someone, free to hold someone’s hand, free to wear a sequined white glove.