New Eelam and the dispersion of critique

Keywords: christopher kulendran thomas, jeppe ugelvig, New Eelam

You’re home everywhere. Jeppe Ugelvig on artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas’ housing startup.

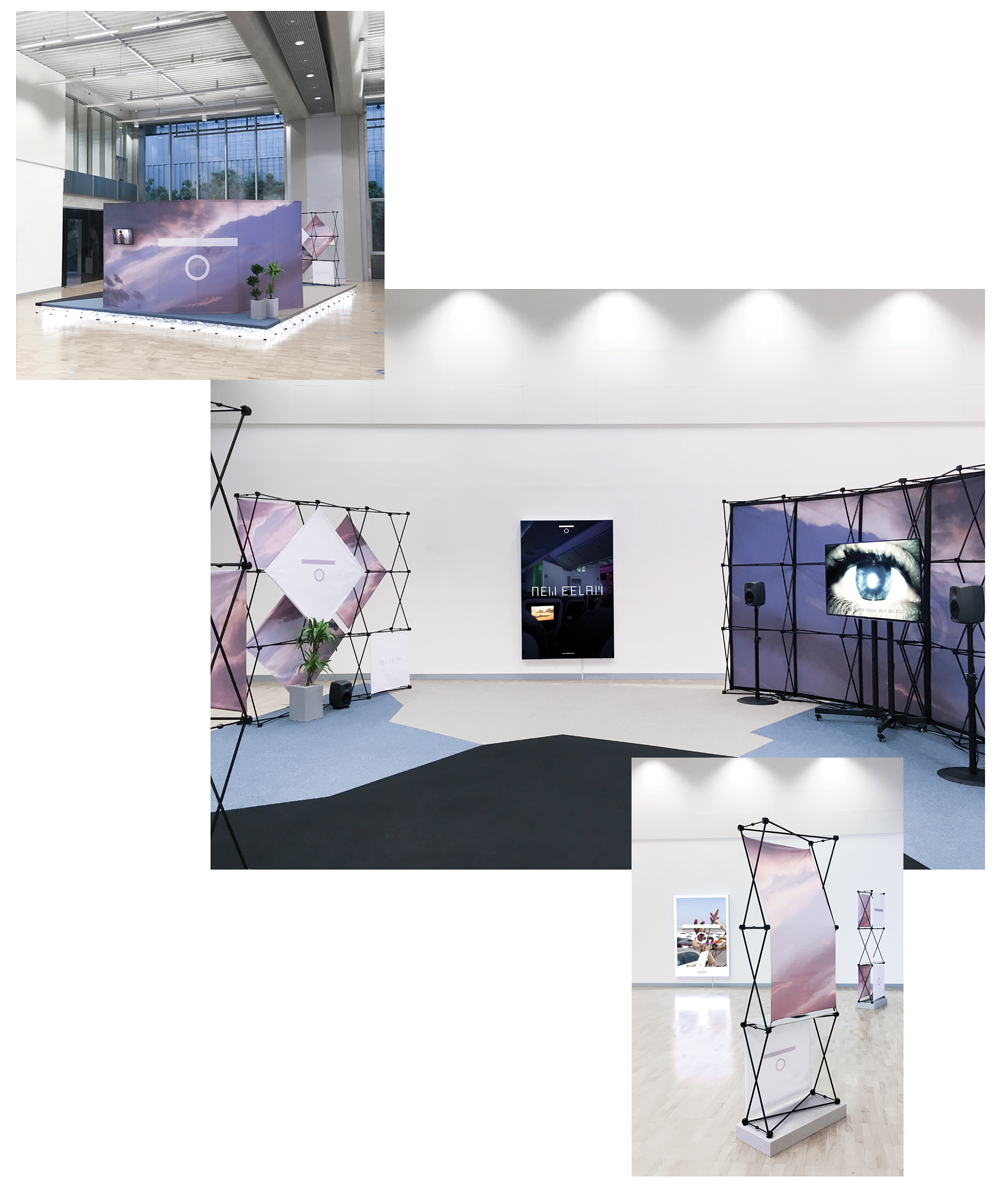

Detail view: Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam advertising, 2016

Design: Manuel Bürger & Jan Gieseking, Photography: Joseph Kadow, Creative Director: Annika Kuhlmann

1. Christopher Kulendran Thomas’ ongoing work New Eelam – developed in collaboration with curator Annika Kuhlmann and initially introduced at the 9th Berlin Biennial and 11th Gwangju Biennale, with a new iteration coming soon to Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin – exceeds the traditional limits of the artwork. Not only formally – the work is envisaged as an open-endedly durational project in the form of a startup – but particularly in its socioeconomic spatiality and critical technique. Rooted in the complicated story of the geographical displacement and genocide of the Tamil people, New Eelam can best be described as a real estate tech company that envisions and proposes new liquid models of citizenship and distributed homeownership in an age of technologically accelerated dislocation.

Installation views, 11th Gwangju Biennale

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

New Eelam, 2016

featuring original artworks by Asela Gunasekara

and Sanjaya Geekiyanage

Design: Manuel Bürger & Jan-Peter Gieseking,

Photography: Joseph Kadow,

Creative Director: Annika Kuhlmann

2. After an American presidential election in which nearly half of the country’s voters at least acquiesced with the rather aggressive displacement of others (incidentally resulting in Canada’s immigration website crashing on election night), questions of belonging seem to be taking on a new global urgency. How can the liberal nation state negotiate increasingly polarized populations? What does a reactionary response to neo-nativism and anti-globalism look like for communities that still pursue dreams of multiculturalism? And where does technology sit within the practicing and delineation of citizenship and the bourgeois capitalist institution of the home?

Installation views, 11th Gwangju Biennale

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

New Eelam, 2016

featuring original artworks by Asela Gunasekara and Sanjaya Geekiyanage

Design: Manuel Bürger & Jan-Peter Gieseking, Photography: Joseph Kadow, Creative Director: Annika Kuhlmann

3. Envisioned as a flat-rate subscription service, New Eelam’s subscribers will gain access to a portfolio of homes “in some of the world’s most charismatic neighbourhoods,” as its promotional video promises, saturated with the quintessential iconography of urban wanderlust, recognizable from start-up advertising. Adopting the closed loop growth model of e-retailer Amazon, 100% of the revenue of New Eelam’s subscribers, along with capital gains from the speculative real estate investments the company makes, are reinvested into an ever-expanding portfolio of properties, effectively lowering the rent while improving the service for users. What will form, imaginatively, is a global network of homes owned by no one and everyone – or as the video promises, “luxury global communalism rather than private property”. As a corporate entity, New Eelam owes its architecture equally to the historical notion of the socialist coop and the contemporary sharing economy start-up, two seemingly opposing structures that nonetheless converge via technology in our contemporary socio-economic reality. With New Eelam, Thomas sees a potentially emancipatory trajectory for technology in the global economy: specifically, the liquidation of citizenship through the dissolution of individual property ownership in a time when capitalism accelerates its way out of its own sustainability.

Installation views, 9th Berlin Biennale:

Christopher Kulendran Thomas,

From the ongoing work New Eelam, 2016

Acrylic on canvas, concrete shelf, LEDs, plant and

‘New Eelam’ film (HD, 14:06), featuring ATLAS bar stool by NEW TENDENCY

Images: Laura Fiorio / Joseph Kadow

4. Beyond the artist’s own biographical relation (Thomas’ family are Tamil and left escalating racial violence in Sri Lanka), there’s a specificity in adopting the history of the Tamil people as a basis for New Eelam. As a civilization, the history of the Tamil people of “Eelam” stretches back over 3000 years, effectively pre-dating the rise of both the nation state and its coupling of citizenship (and hence, any definition of legitimate geopolitical ‘belonging’). Colonial rule left the Tamil people governed by an ethnic majority backed by foreign governments, leading to the exclusion of Tamils from academic positions and civil service jobs in the Sri Lankan public system. After a long and bloody civil war, in which more than 300,000 Tamil people were internally displaced and tens of thousands of civilians were brutally murdered, the idea of Eelam (an independent, gender-equal socialist state) fully collapsed with the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in 2009. This sudden “peace” paved the way for aggressive foreign investment and Western tourism in Sri Lanka. And, as Thomas himself describes, “in the immediate aftermath of that violence, and the consequent economic liberalisation that followed, a new local market for contemporary art emerged.” Thomas’ exhibitions feature original artworks by some of Sri Lanka’s foremost young contemporary artists, purchased recently in that ‘peacetime’ economic boom and then reconfigured by Thomas for international circulation within his own compositions. His work manipulates some of the structural operations of art, the means by which its circulation and distribution produces reality. This ongoing operation translates what counts as contemporary across the global contours of power by which the ‘contemporary’ itself is conditioned and draws on the outward performance of democracy by which nations evade international accountability. Put differently, the story of Eelam is also a story of the subjugation of socialist communities to destructive global capitalist market forces and their colonial genealogies. The story of New Eelam, on the other hand, is an attempt to reimagine community through and beyond them.

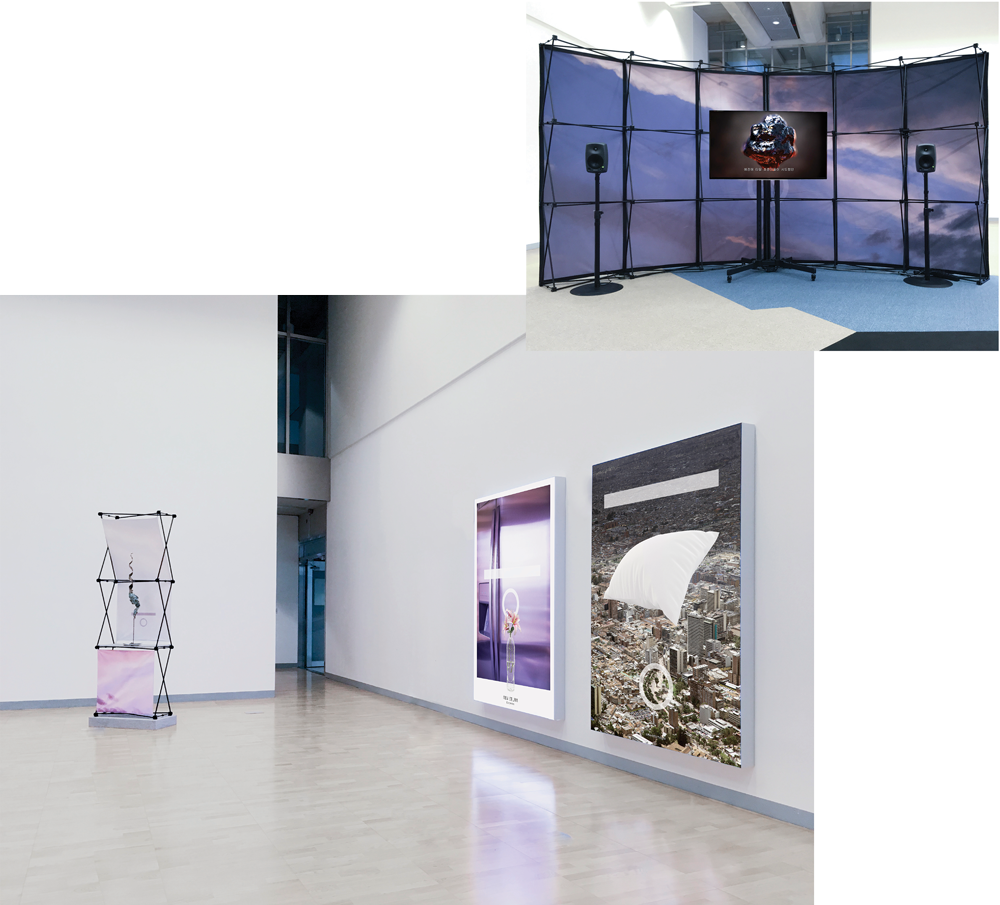

Installation views, 9th Berlin Biennale

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

From the ongoing work New Eelam, 2016

Concrete, one-way mirrored glass, biosphere, LED, fridge, bottled water,

leaflets and 45s silent lift from ‘New Eelam’ promotional film

Images: Laura Fiorio

5. While much of the art that engages so-called “corporate aesthetics” is both critiqued and legitimized as operating through speculative ‘fictions’ and as employing satirical ‘artifice’ (as observed in much of the polemical criticism around the 9th Berlin Biennial), there is nothing fictional about New Eelam – in fact, it already exists as a company in its early phases of prototyping it’s beta edition. While it speculates upon future potentialities for forms of living and working through technology in a seemingly “surreal” or “hyperreal” way (to rely on relatively outdated modes of aesthetic judgment), its cultural, political and economic trajectories are very actual, that is to say concerned with the actuality of contemporary conditions of living and working in a globalized economy. Rather, perceiving the engagement of corporate aesthetics as ‘artifice’, it points more than anything to the synthetic texture of our everyday lives. This synthetic component to New Eelam is central to its success, as it echoes its (post-)critical trajectory of powering through ever-morphing capitalist institutionality in all its visuality, rather than circumventing it: “to outcompete the present economic system on its own terms,” as the narrator in New Eelam’s promotional video explains. As a meditation on the failed revolution of historical Marxist states (like Tamil Eelam), as well as on the commodified and nullified status of leftist critique at large, New Eelam envisages a form of autonomy beyond neoliberal capitalism by accelerating the existing system’s own unravelling. If the global market economy absorbs and distributes every aspect of human life, and transcends national borders and laws (as seen with multinationals such as Apple and Amazon, the latter of which is poignantly analyzed in New Eelam’s long-form promotional video), why not use it as a tool for critical and subversive agency? In Thomas’ work, the future of the political Left lies in a mutation of capitalism’s own accelerated state of being. This, of course, is no small proposition and contains its own set of ethical conundrums.

Installation views, 9th Berlin Biennale:

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

New Eelam, 2016

HD, 14:06

Images: Laura Fiorio / Joseph Kadow

featuring TILT storage device by NEW TENDENCY

6. The avant-garde impulse in Thomas’ practice is echoed clearly in the “New” of New Eelam, adding a constructivist and, arguably, even utopian dimension to the work. While New Eelam is “more than art” – that is to say concerned with some form of life beyond the world of art – art remains the starting point and recurring cultural habitat for the project (it starts as a biennial commission and will return to art world platforms when appropriate). Why? As history exemplifies, it is in art that we find the most innovative prototyping of immaterial labor. Ambivalently, art’s ever-mutating labor dynamics facilitate a discursive platform for imagining new labor futures, both constructivist (and potentially revolutionary) as well as co-optable for businesses. We see this when strategies from conceptual, post-conceptual, and performance art are adopted by advertising firms and start-ups in the global experience economy, which in turn are recouped by artists, adopting rhetorical or economic strategies from globalized capitalism (fashion, business, PR). If the home is a primary site of labor in a post-work automated future, it is only natural that its early precursors are found in contemporary artworks.

Installation views, ‘60 million Americans can’t be wrong’

at Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof:

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

New Eelam, 2016

featuring original artworks by Asela Gunasekara, Muvindu Binoy and Prageeth Manohansa

Images: Michael Pfisterer

7. It was once widely assumed in Silicon Valley that one needed an MBA to start a company, but with the rise of technology-based consumerism, this was superseded by the engineer founder (Facebook, Google), and more recently, in line with the increasing sophistication of the consumer internet, designers are starting big companies (AirBnB, Instagram). Could this perhaps now be the time when an artist starts a successful high-growth tech company – on artistic and critical terms – and if so, how would their critical apparatus translate into a socioeconomic reality? As Thomas has argued elsewhere on DIS, this shift would entail a departure from the ecology of the art system into a larger ecology of (or even beyond) capitalism[1] – one in which work depends on “reproduction and distribution [in the …marketplace] for its sustenance,” as Seth Price once put it.[2] At the brink of neocapitalism,[3] in which complicity is inevitable and any form of autonomous critique only strengthens the ties around the political subject, the point, as David Joselit argues, is not to deny the power of the market, but to use this power.[4] The strategy of full immersion into capitalist production, giving up any leftover dream of bourgeois art-making, has been hinted at and even experimented with by artists – Renzo Martens, DIS, Shanzhai Biennial, amongst others – but until now, never fully realized. Like all avant-garde practices, in its attempt of embedding itself into a capitalist logic, New Eelam will always risk its own status as an artwork; but isn’t this exactly what the most interesting art has always risked?

Installation view, ‘60 million Americans can’t be wrong’ at Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof:

Christopher Kulendran Thomas

From the ongoing work When Platitudes Become Form, 2016

Acrylic on canvas, wooden frame, netting and ‘Lord Ganesh’ (2011) by Dennis

Muthuthanthri. Image: Michael Pfisterer