Solastalgia

Keywords: ada o'higgins, Bea Fremderman, born nude, Interview, solastalgia

Bea Fremderman imagines a world after all is lost

There is a place you call ‘home’. A place you leave in the morning and return to at night. But when you walk through the door, nothing is how you left it. And your once familiar clothes are overgrown, corroding on a body, which itself feels foreign.

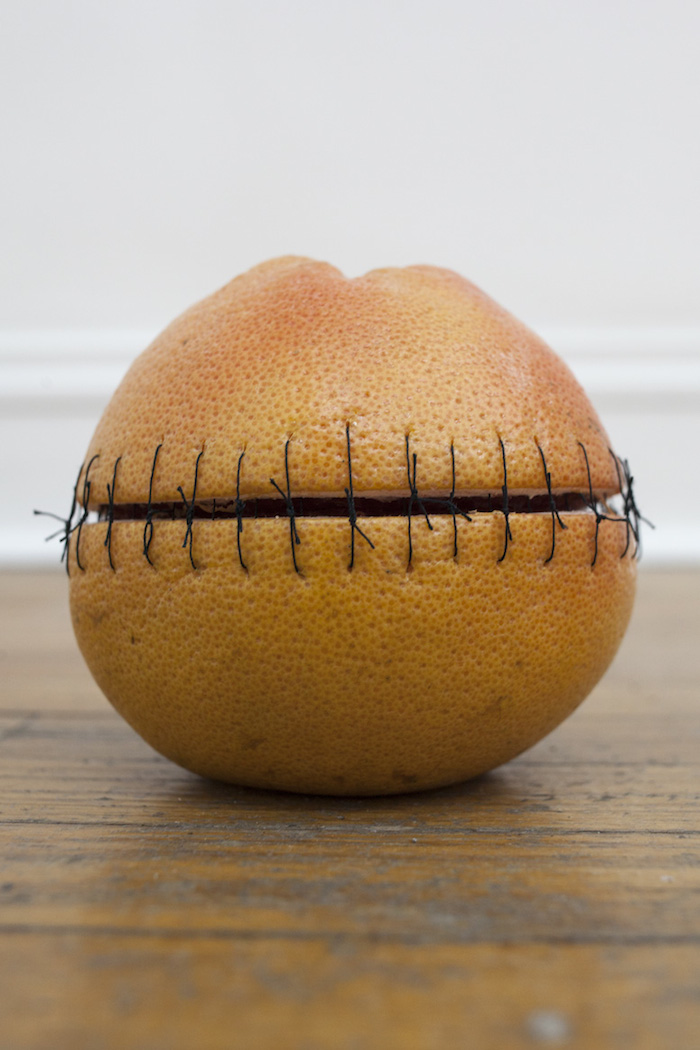

In Solastalgia, running through February 27 at Born Nude, Bea Fremderman imagines a world after all is lost. Hoodies and socks disappear beneath chia sprouts, fruits are barely held together by sutures, and bowls are made of dryer lint, making you wonder: if every object around you was a reminder of an impending ecological disaster, would you act differently towards the earth?

Ada O’Higgins: Can you explain the term ‘Solastalgia’?

Bea Fremderman: Solastalgia is a portmanteau of the words ‘solace’ and ‘nostalgia’. It’s a term coined by Glenn Albrecht that “captures the particular form of psychological distress that sets in when the homeland that we love and from which we take comfort is radically altered by extraction and industrialization, rendering it alienating and unfamiliar.” It is the homesickness you feel when you are still at home.

How does the show develop the themes you explored in Hindsight is 20/20?

Hindsight is 20/20 dealt with issues of consumption and labor. That show was definitely a springboard for Solastalgia. More specifically, there was a piece in Hindsight titled Hungry Bellies Have No Ears which was a sculptural triptych consisting of three acrylic boxes held together with gold screws separately encasing gold electronic scrap, a gold bullion bar and a gold dental crown. The piece is a recycling of obsolete technology back into its original elemental state and then into a functional object once again. It shows the versatility of a material and how in different states it can be perceived as useless, valuable and functional. This interest dovetailed into the work I made for Solastalgia.

Do you experience this feeling of dread in relation to ‘eco-anxiety’ on a daily basis?

I think my eco-anxiety has transformed into eco-paralysis. Meaning that I know the ecological problems that we are facing are larger than what we can control and I’m really unsure what to do about it on an individual basis. Changing my light bulbs, recycling and taking public transit can only do so much at this point. Only a much larger, top-down change must happen in order for us to prevent our planet from warming further.

How do you see your work and art practice in relation to the feeling that the direction the world is moving is beyond our control? Is it born out of hopelessness or hope?

I think my interest is born out of hope. Foreseeing or hoping for an apocalyptic ending is really a deep desire for a radical societal change.

There are garments in the show, but you seem to approach them not from a fashion perspective but from the perspective of their ephemerality and decay as possibly a symbol for other things. What led you to use garments in this show?

I spend a lot of time thinking about how nature prevails against all odds. When I first moved to New York I was really taken aback by these trees in Bedstuy near my studio that had grown through a wrought iron fence. The tree just kept growing around this man-made object as if it wasn’t there. That image has stuck with me. The chia covered clothing transforms itself out of fashion and into a symbol for the human body and our possessions. Clothing is meant to keep us protected from nature but it is obvious that nature does what she wants and is superior to us in many ways.

Tell me more about the materials you used in the show! The materials and textures seem very organic yet you’re commenting on a situation that is partly due to society’s technological advancement. What drew you to these materials in particular?

The 15 stacked bowls were made out of dryer lint that I had prepared into a clay and then shaped into form. I was really drawn to the idea of making potteryware out of dryer lint because I like this idea of taking something that is unintentionally recycled and creating anew. Lint is the residue of clothing bundled up from a variety of fibers among other smaller particles, including human and animal hair, skin cells, plant fibers, pollen, dust, and microorganisms. I chose to make potteryware because early potters used whatever clay that was available to them. In my post apocalyptic setting this seemed right. The lint bowls were not made from the earth but from the mess we’ve created and that’s kind of beautiful to me.

What’s it like to work with materials that seem to corrode with time?

I knew I was working with ephemeral materials when I started the project and part of the process was seeing what would happen in time with the objects. What I found interesting is that I was using materials as metaphors for how nature takes over humanity and in the end nature did in fact take over the work and did what it wanted with it. The chia on the clothing died; the fruit dried causing the sutures to loosen up or tighten depending on the fruit; mold grew on the lint bowls and finally the brick wall sprouted enough cherry radishes that it uprooted the wall and partially collapsed. I knew the exhibition was going to change and there was nothing that I could do about it. That really adds to the show. Change is part of it, decay is part of it. Instead of seeing these changes as elements that take away from the work, I see them as an additive-process.

Do you think you’ll see your designs on the runway next season?

Yeezy x Bea Fremderman

Text Ada O’Higgins

Images courtesy Born Nude

Bea Fremderman, b. 1988 Bea finished her studies at The School of the Art Institute in Chicago. Her current research interests are the economic impacts of climate change, apocalyptic survival tactics, feelings of global dread and false notions of freedom. Upcoming exhibitions include Springsteen Gallery in Baltimore.