Art and Capital

Keywords: Art, capital, olav velthius, Sarah Lookofsky

The art market is not actually booming. Olav Velthius and Sarah Lookofsky talk it out.

The art market is not actually booming. Sociologist Olav Velthuis puts the artworld’s economic misconceptions to bed with Sarah Lookofsky.

Sarah Lookofsky: Olav, you have argued that the popularly cited art market “boom” is overstated. In your analysis you describe instead a “winner-take-all” boom that only affects top players: a dramatic rise in money exchanged by the highest collectors concerning the work of very few artists, represented by a small group of galleries. Ultimately, conditions remain largely unchanged for most sectors of the artworld.

I have read persuasive reports which state that the rise in inequalities neatly tracks those sharp art market increases. This leads me to wonder if the misrecognition of a widespread boom you describe is related to another misrecognition in which dramatic wealth increases at the very top have been taken to mean prosperity overall. This seems, to me, related to your correction of another art market cliché: the celebrated “global” art market belies the near-complete dominance of just a few global national economic players. What are some examples of these very few players and what do you think of this comparison?

Olav Velthuis: I absolutely agree that for a number of decades, roughly since the 1980s, economic inequality was a non-issue; it was not part of the public imaginary. In my own discipline, sociology, it was not very fashionable to study income or wealth inequality. My impression is that this has changed. Think of the huge success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital, which points to the dramatic rise in inequality in Western societies. People now seem to realize that the extraordinary wealth that is being accumulated by a small group of multimillionaires and billionaires (or, as consultancy reports refer to them, “High Net-Worth Individuals”) is not trickling down to the bottom of the income distribution. For poor families in many Western societies, wages have decreased in real terms over the last decades.

I am not certain that people are equally aware of inequalities in the art market. When I talk to art dealers, many complain that outsiders these days think business must be strong for them. They have read the headlines about record auction prices or about the next magnificent, museum-like space some powerhouse dealer is opening, and automatically assume that everybody working in the contemporary art world is doing great. Whereas, in fact, many gallerists are having a hard time staying in business: their costs have risen (e.g. because of rising real estate prices or expenses related to participating in art fairs), but their profits have hardly increased, since this new class of superwealthy do not visit them. The same goes for artists. To give a concrete example: Artprice, a French firm which collects and sells auction data, annually publishes a list of 500 artists based on the earnings of auction sales. Of all the living artists born after 1945, Jeff Koons topped the list. Last year 52 of his works sold at auction for 115 million euro in total. The person lowest on the list was a Danish artist, Sergej Jensen. Four of his works sold for no more than 256.000 euro in total. In other words, Koons’ works sold for almost 500 times as much at auction. And Jensen is still quite well off: he is part of the top 500. So you can imagine how big the difference in income is between Koons and your average artist in the US, Italy or China whose work hardly ever sells in a gallery or at auction. In short, a tiny group of artists is getting fabulously rich while the vast majority hardly earns anything. Although there is no good data available to prove this, my impression is that the split between the 1 percent and the 99 percent is even bigger in the art market than it is in the rest of the economy.

SL: You write of a “moral panic” regarding the most common reaction to the art market. Do you see it as related to these inequities?

OV: I see these economic inequalities as only indirectly related to the moral panic about the so-called flippers who buy and sell new, contemporary art in a high-pace, speculative manner. I think this moral panic is a manifestation of a deeper unease about the relationship between art and commerce, which has been part of the art market’s culture since at least the 19th century. The panic is triggered by these flippers, and then amplified by the media who delight in writing about them. However, had it not been for the flippers, the panic could have been triggered by some other new character entering the market. In fact, the panic surrounding flippers already seems to be over. Now, it is more focused on billionaires in the Middle East and China who snap up masterpieces at auction and by doing so crowd public museums in the West out of the market.

SL: The artwork’s position in the market causes a lot of confusion and anxiety–often, I think, fueled by vague notions of “commodification” (the idea that something with character loses its properties once sold on the market). But the art object doesn’t perform like a commodity proper, like wheat for example, where one unit of the material can be swapped with any other unit. Instead, many have likened the artwork to a rare luxury product, akin to an antique piece of jewelry or a select car model. Based on your sociological study of how people relate to these things we call art and how those things perform on the marketplace, how do you find it useful to conceive of artworks?

OV: As a sociologist, I find it interesting to see and study how societies categorize all kinds of goods that circulate. Obviously, at least since the Renaissance, art has been considered a special category, as a type of good that deserves special treatment (part of which is that it cannot be commodified in the same ways as other goods). But if you look at it more factually, the differences between art and other goods are not always that big. Of course, artworks are unique. But in our consumer society, companies are doing their best to “singularize” many other goods, and consumers try to use them in unique ways as well. Just think of clothing. Moreover, many artists keep producing the same, or highly similar, works of art for a variety of reasons (because they are obsessed with them, because they know those works will sell, etc). So you may say they churn out commodities… which are not very unique. And finally, I question how important uniqueness is for many buyers in the art market. They are looking for something to decorate their house with, something that will confer status on them, or something that will function as value storage. Many artworks fulfill those needs and are therefore, for some buyers, to some extent interchangeable. In short, the actual difference between a work of art and other goods may at times not be that big. But in the way we think about and classify goods in contemporary society, we continue to create separate categories and construct strong boundaries between art and non-art. The organization of the art world is founded on those categories and boundaries. Otherwise, art could also be available for sale in a department store.

$186,000,000

SL: I know that many artists would find difficulty with this sort of analysis equating artworks to other customized commodities–especially artists who conceive of their work as operating politically or critically in relation to those very market forces. To parse this point, one can compare artistic practice to your research as an academic, which results in texts that are included in books that are sold. Nevertheless you would probably argue that the content of those texts can somehow be considered in other terms than their economic value. Does this commodity model, and other analytical tools that give precedence to the art market, preclude comprehending artworks as originators of meaning, I wonder?

OV: This commodity model absolutely does not preclude comprehending artworks as originators of meaning. But it is simply not what I am interested in, at least not in my recent research. A while ago I wrote a booklet about those meaningful, critical dimensions of contemporary art: I tried to interpret contemporary art as a meaningful source of economic knowledge, which provides an alternative to hegemonic, neoliberal or neoclassical economic thinking–I called this contemporary art imaginary economics. But currently, as an economic sociologist (which is what I consider myself to be: an academic interested in social and cultural aspects of economic life), it is this commodity form which fascinates me. The art market provides for me a way to understand how markets operate more generally in contemporary societies. I think it is important to try to develop rival understandings of markets to the hegemonic ones, which pervade both economics and popular thinking, in which markets get reduced to e.g. “the forces of supply and demand” or to rational individuals trying to satisfy their self-interest. Markets are so much more complex. The art market demonstrates that clearly. So I do not want to say that art in contemporary society only circulates as a commodity or that all value of contemporary art can be reduced to economic value. I am very well aware that there are many artists who are not part of and do not want to be part of the market, and I fully understand that. Indeed, as an academic, I am not only interested in how many copies of my book sell or how frequently my articles get downloaded or cited. I am interested in engaging in relevant, interesting or critical debates.

Commodification is very important for the way I think about how the art market works. I use the term not in the Marxist but in the anthropological sense, following the work of Arjun Appadurai. He points to the big differences in the way we transform goods into commodities, how we do it, when and where we do it, what type of physical spaces enable this transformation, etc. To make it more concrete: given that we think of art as a special category, as a unique good, as a “non-commodity”, it can only be commodified under special circumstances and in highly ritualized ways. That’s why the commercial art gallery has to look like a museum, where references to commerce are suppressed, as opposed to a supermarket. That’s why the opening party of an exhibition is so important; it ritualizes the transgression of a work of art from the non-commercial studio space of the artist to the commercial gallery space. That’s why people are so upset about the flippers and other speculators, or about auction houses focusing more and more on contemporary art: they violate the norm that art cannot be transferred into and out of a “commodity phase” repetitively. Yes, art can be turned into a commodity, but compared to many other goods the freedom people have to commodify art is relatively limited. Of course, due to the internet and wider processes of financialization and commercialization, among other things, the culture of the art market is changing as well, but not as quickly as other markets due to the resistance it provokes.

SL: I am also curious to hear your take on the highest grossing grossing items, the very top of the market. Can you discern any unifying or distinguishing characteristics that set them apart?

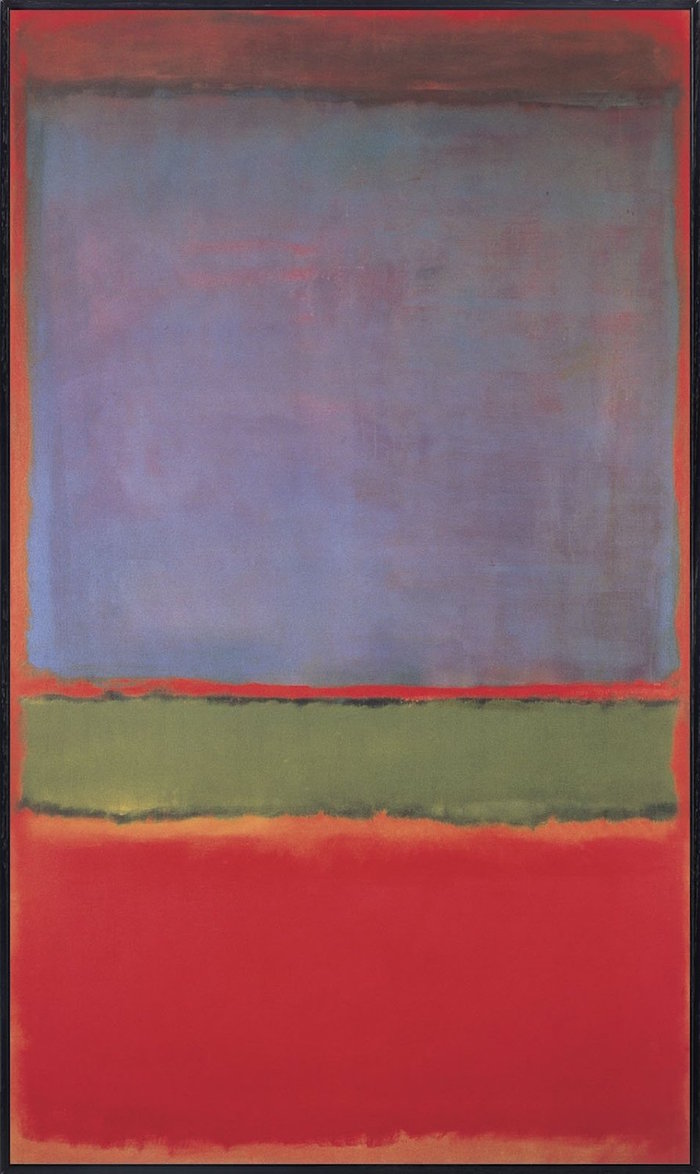

OV: What is striking is that there are very few old masters among them, but that is of course also because very few important old master paintings appear on the market, as they are fixed in museum collections. You can think of them as “terminal commodities”. Another striking aspect, which goes against all the talk about the contemporary art market’s extraordinary boom, is that among the absolute top, the 50 most expensive works of art, there is not a single work made by a contemporary artist. Not even Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog, which to date is the most expensive work of art made by a living artist. The vast majority of the most expensive works were created between 1890 and 1970. The artists (Picasso, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Warhol, Rothko, among others) are old enough for them to have an established permanent position in the art historical canon, but young enough for their works to still be part of private collections, and therefore still to appear on the market. Another characteristic: almost all of these works are big. You do not find small, intimate pieces at the top. Why not? Because these pieces obviously serve to signal status. They must have “wall power” as they like to call it within the art market. I would say that they all have some decorative quality; they cannot be too disturbing. But for the rest, it is a very mixed bag.

SL: Your recent research concerns the art markets of the BRIC countries. Since the countries were brought together in that acronym for being the fastest-growing market economies, I am curious to hear if Brazil, Russia, India and China are also somehow relatable in terms of their art markets? In other words, is there necessarily a correlation between the larger economy and the art economy?

OV: There is definitely a correlation, but the ways in which the larger economy impacts the rise and survival of the art economy differs greatly in those four countries. On the one hand you have Russia whose local art market has been doing poorly over the last decade. One reason is that wealthy Russians tend to live, or at least enjoy their leisure life, outside of the country in London. That’s where they spend their money. They try to create a rather cosmopolitan identity by means of collecting art and therefore buy Western-European and American artists, not Russian artists. As a result some of the main galleries in Moscow have had to close or change course dramatically. The other extreme is China, where there is a very rich, old, collecting culture, which has been reinvigorated from the 1990s onwards by the booming Chinese economy. Combine that with a strong sense of patriotism and you get a booming, local art economy. However, many of the Chinese artists, whose work does very well in the local market, are completely unknown abroad. For instance they make realist oil paintings, which we think of as rather kitsch in the West. In short, although some counterexamples do exist (e.g. Berlin in the 1920s which was poor but had a very lively art scene), you do need a flourishing economy overall in order to have a strong art economy. But it is a necessary condition, not a sufficient one. There are other social and cultural parameters which determine if and how economic wealth translates into a flourishing art scene.

SL: For instance, without any basis in data, I should note that I have sensed a sudden preponderance at biennials (arguably the most “global” exhibition format) of artists from nations with growing economies. For example, I sensed a sudden multiplicity of Brazilian artists a few years ago compared to a total absence of artists from poorer South American countries…

OV: There is a relationship between economic performance and cultural domination, but again, I would like to warn strongly against the type of–implicit or explicit–economic reductionism that you find in a lot of popular talk about the contemporary art world. For it is definitely more than economic wealth that counts. For instance, Brazil has been doing particularly well (probably, in terms of international recognition, I would say few countries outside of Europe and North America have been doing better than Brazil) in the global art field for a number of reasons. It has a rich and long history of modern art, with movements such as neo-concretism, which can be understood as a forerunner of conceptual art. The São Paulo biennale, the world’s second biennale, was founded in 1951. From the late 1940s on modern art museums have been established in the country. Its gallery scene dates back much further than those of China or Russia. A gallery like Luisa Strina has been participating in Art Basel since the early 1990s.

SL: To the extent that art does travel beyond national boundaries, I wonder if there is usually a direct relationship to economic indexes?

OV: In statistical analyses, which I have conducted, I find that economic wealth matters, but many other factors do as well. For instance, one type of cross-border traffic I have looked at is between artists and galleries: I try to understand why so many American artists are represented by German galleries, for example, and why so few Chinese artists are found in Brazilian galleries. Apart from wealth and population size, geographic distance is an important factor: the greater the distance between a country where an artist was born and a country where a gallery is located, the less likely it is that the gallery will represent that artist. The same goes for what I call cultural distance: if two countries have for instance a shared colonial history, or if the same language is spoken, it’s more likely that artists and galleries from those countries will cooperate. Which is unsurprising if you realize how important face-to-face contact between artists, gallerists and collectors remains in the contemporary art market. In the end, the art market is above all a communications market.