Ian Bogost | Funemployed Playborers

Keywords: Attent, attention economy, brogrammers, data obesity, flexible, flexible labor, flextime, flexwork, funemployment, gamification, Go Fucking Do It, HabitRPG, hyperemployment, ideology, information overload, object-oriented ontology, OOO, play, playbor, Serios, Seriosity, speculative realism, startups, telecommuting, video games

Media critic and video game engineer Ian Bogost talks flexwork and ideological gamification.

Dr. Ian Bogost is an award-winning author and game designer whose work focuses on videogames and computational media. His games about social and political issues cover topics as varied as airport security, consumer debt, disaffected workers, the petroleum industry, suburban errands, pandemic flu, and tort reform. His games have been exhibited internationally at venues including the Telfair Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville, and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. He is Ivan Allen College Distinguished Chair in Media Studies and Professor of Interactive Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology, a Founding Partner at Persuasive Games LLC, and a Contributing Editor at The Atlantic.

Marvin Jordan Your work is affiliated with a contemporary philosophical movement known as object-oriented ontology, stylized as OOO, which sets itself in critical opposition to the history of philosophy. On the other hand, as a video game engineer and media critic, your work also appears in fields outside of academia, in more practical and publicly accessible contexts. Could you break down the basic premise of OOO and how it relates to your practical work? Can it open a new way of understanding our relationship to technology?

Ian Bogost Object-oriented ontology (or OOO, which, via Timothy Morton, I like to pronounce as “triple-O”) is a branch of philosophy that originated in and then split off from a loosely-tied group who called themselves “speculative realists.” The speculative part of speculative realism accepted the need for non-commonsensical approaches to metaphysics. The realism part rejected not just the idealist tendencies of metaphysics since Kant, particularly what one of the original speculative realists Quentin Meillassoux calls “correlationism,” his name for philosophies of access. That is, for the idea that the world only exists in conjunction (or correlation) with human thought or perception.

There are various interpretations of OOO, but the fundamental premise of this branch of speculative realism is not that humans have direct access to things-in-themselves, but that, actually, (a) nothing does and (b) the correlation between human and world that Kant insisted upon and that has persisted since is not a special property of humans but a property of and between all things. This move puts everything on equal footing, metaphysically speaking (although various practitioners of OOO have differing views on what that means). I embrace what Levi Bryant has called “flat ontology” (a term he borrowed from Manuel DeLanda, and which could equally apply to Bruno Latour). In my book Alien Phenomenology I offered this gloss on the concept: all things exist equally, but they do not equally exist. That is to say, the existential equality among things.

So, you can think of OOO as a philosophy directed toward “things,” but in which “thing” or “object” or whatever term you want to use (I have used “unit” as a less historically and philosophically charged version) refers to anything whatsoever — including actions and processes, not just toasters and furnishings. Once we accept the premise that everything exists equally and that everything has the same limited access to the full nature of all the other things with which they interact or come into contact, then we have the opportunity to theorize about how exactly things do relate and understand their private universes. For my part, I’m particularly interested in the idea of an object’s experience — that things have something akin to experience, but that would be very different from the kind of thing we consider experiential from our human vantage point. Thus the idea of alien phenomenology — a speculative account of how things perceive, based on our best attempt at finding and poeticizing the evidence or the “exhaust” those units provide to help us understand their molten core, to borrow a term from the OOO philosopher Graham Harman.

This last point helps answer the second part of your question. I had always been connected to contemporary philosophy, particularly contemporary continental philosophy, and I had been reading Harman’s work long before “it was cool.” But I didn’t return to that work directly until I began working with Nick Montfort on what would become Racing the Beam, our book on the 1977 Atari Video Computer System. This would become the first book in the Platform Studies series that Nick and I co-edit at the MIT Press. The premise of that series is analysis of the relationship between the technical design of computer platforms and the creative and cultural results of those systems.

As Nick and I began working on our history of the Atari, I also learned to program the machine, partly just because, and partly because we needed to know a good deal about how the hardware worked to write a material history of it. It’s a very weird computer—I’ll spare your readers most of the details, but one of the Atari’s most unique characteristics is that the programmer has to interface with the television picture on a scan line-by-scan line basis, rather than setting up a screen’s worth of image. Nick and I had focused the book series on how computer platforms influence and structure human creativity, and that commitment continues.

When I started looking closely at the weird, unseen dynamics created by the various components at work in the Atari—the cathode ray tube’s electron guns, the phosphor that coats the back of its screen, the custom-designed integrated circuit that interfaces between the Atari’s microcontroller and the RF adapter that modulates signal to the television—I realized that I was just as interested in their experience of one another as I was in the player’s experience of them as a collective. And furthermore, that paying deliberate and careful attention to these components was making me a better critic and a better game designer (yes, I actually make Atari games, even 35+ years hence).

It was that realization that sent me back into philosophy in general and OOO in particular. Two things were clear to me: first, that the nature and experience of anything is worthy of philosophical study, and not just as gimmick. And second, that this kind of careful attention to materials for their own sake has much pragmatic use for creators and practitioners of all kinds. This is perhaps why OOO has been so well and widely received among the arts, architecture, games, technology, and other creative communities.

MJ Much of your writing has been dedicated to demystifying dominant preconceptions about video games in our culture. According to the prevailing narrative, video games are primarily entertainment-centric and leisure-based, which you regard as “a testament to our deeply ideological relationship with play.” As a primer to your work, could you clarify how we may begin to develop new criteria or categories of video games that go beyond the binary of serious-fun or work-leisure? What would a less or non-ideological relationship with play look like?

IB In my book How to Do Things With Videogames, I talk about the idea of media maturity. In mature media — photography, writing, the moving image — you see many uses of a medium in a broad array of contexts. You can use photography for art, for journalism, for personal record, for surveillance, for pornography, for personal reminders, and much more. These uses evolve over time, slowly, accreting from multiple origins like a moon forming in orbit of a planet. But that maturity of use is part of what makes media become mass media — by which I mean, ordinary media.

Marshall McLuhan calls it “ground” — the things we don’t even notice, but that structure the things we do (what he names “figure”). We often think that new media are exciting or “disruptive” and that this is why they become and remain appealing. And it is, at first. But in order to become mass media, all new media must become ordinary. Otherwise they remain curiosities, and as curiosities they have less capacity to be broadly influential.

So in games, one of the ideas about expanding their influence has always involved making them more “serious,” using them in contexts just the opposite of leisure and entertainment. Education, business, governance, health, and so forth. And these are fine ideas, and indeed they are domains in which I have myself made games for various kinds of organizations over the years. But the media ecosystem is not a binary switch that’s either set to “respected” or “scorned.” It’s a spectrum, and the more the spectrum fills out, the more grounded the medium becomes. So we want to keep the “entertainment” uses of games, but we want to break those down into their components, and the serious ones too, and everything in between and all around those arbitrary categories. The way games become mature is opportunistically, by entering culture at every turn they are offered.

Children’s Games, 1560, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The quote you pulled is from my first book, Unit Operations, which was meant to underscore how games and fun and play are usually considered unproductive activities of excess. My thinking about play and fun has evolved since then, and I’m writing a new book on those subjects. But the business of an ideology of play remains well-defended broadly speaking. Usually we see it discussed in reference to childhood development, and particularly as a needed counter-balance to massively structured, measured schooling, especially in contemporary America. Or alternately, you hear play brought up as a necessary activity for adults as much as for children (think of Stuart Brown, for example). But these ideas still assume that play is an escape, an exception to the work of working. But play is actually something far more general—it’s the feeling of operating something. And in that sense, games (and other playable media) have the opportunity to help us pay closer, more careful attention to the world around us—not just as a temporary relief from serious business.

MJ You have written that “No matter one’s perspective on the state of capitalism today, games have not yet made much use of branding as a cultural concept.” Taken from your book “How to Do Things with Video Games,” this observation underscores the ‘social realism’ or extra-economic function of existing brands: the fact that, whether one likes it or not, to ignore the omnipresence of brands in society is to ignore reality. When it comes to games, however, I imagine that the ‘appropriation’ of brands may run into legal trouble, as often happens in art, for example. What was your experience like in relation to Fedex and Kinko’s when you created the game “Disaffected!”? Do you think video games are an apt medium for culturally progressive gestures such as copyright circumvention?

IB So, for backgrounder, Disaffected! was a game about being a disaffected employee at Kinko’s. It was made years ago now, and among the more interesting outcomes of the game was the fact that a Kinko’s Workers organization, kind of a proto-would-be-union, picked it up as a kind of standard for their cause, for their complaints against management.

screenshot from Disaffected!

Back then — maybe 2006 or so? — we didn’t have the distribution channels for indie games that we do today. So we just gave the game away, and we had a disclaimer at the beginning. Had we charged for it, it’s possible that Kinko’s would have sent a cease and desist, but they just ignored us. I do think they knew about the game, as it got some good coverage, including in Businessweek. But brands are smart, and they realize that ignoring criticism is often their best move.

The same was true for Molleindustria’s send-up of global fast food, McDonald’s Videogame. They used the logo and the name, and still to this day you can play it online without disruption. So, there’s plenty of room for culture jamming and adbusting in games, but like all such work, they are probably destined mostly to reach players who already share the political views espoused in the games. PETA has even made some fairly prominent counter-corporate games, focused on animal rights. Some of them have borrowed brazenly from existing games, to the point that they might have risked copyright infringement (I think of Cooking Mama: Mama Kills Animals, for example).

Perhaps the greatest exception is Apple, which has regularly refused to list on or pulled games with political messages from the App Store. Molleindustria made one a few years back called Phone Story, about the dark underbelly of the manufacture of electronic devices like the very iPhones on which the game was meant to be played — coltan mining, suicidal Foxconn workers, and so forth. Apple wouldn’t allow it on the App Store, but you can play it on Android.

MJ In your analysis of what you call “performative gameplay,” which involves play-actions that change the state of the world through mixed-reality game mechanics, you emphasize the importance of consciousness when it comes to the real world effects produced by this kind of play. For example, the physical changes induced by Wii Fit are quite different from those triggered by World Without Oil: one is muscular, the other social. Therefore you state that “outcome alone is an insufficient criterion” for assessing the value of performative games, and that “the player must develop a conscious understanding of the purpose, effect, and implications of his or her actions, so that they bear meaning as cultural conditions, not just instrumental contrivances.” Your words immediately sprung to mind when I came across two new games recently: HabitRPG and Go Fucking Do It. Do you think their respective slogans — “Gamify your life” and “If you fail, you pay” — represent a reactionary moment in gaming today? How do they fit (or thwart) your framework of performative gameplay?

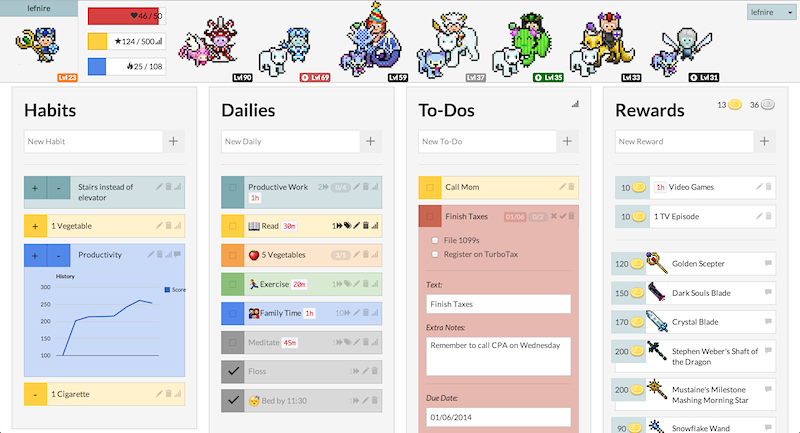

HabitRPG

IB HabitRPG is an app that claims to provide external motivation to improve life habits, by tying them to RPG genre conventions like leveling, hit points, equipment,and so forth. It offers a pretty standard version of a design pattern that’s been called “gamification” — adding “game-like elements” to “non-game contexts.” It’s mostly consulting snake-oil, and it badly misunderstands the primary features of games — simulated experiences with systems — and instead mistakes secondary or borderline irrelevant features for primary ones, points and rewards and the like.

Those who would advocate for such an approach are essentially committed to the position that the ends justify the means. If an app helps you keep your habits, and your habits are good, then the app is good in helping you keep them. But the problem is this: unlike a game whose play itself causes you to exert your body physically, a game that offers external motivation for your habits doesn’t really help you culture those habits. Instead it changes them, it reframes them as the mechanism by which reward can be accrued. Alfie Kohn and others have made compelling arguments against the efficacy of gold star-type programs, showing that they demotivate over the long run. But we don’t even need to consider the psychological implications of rewards to understand that something we do under the structure or those rewards is, by definition, something fundamentally different from doing the thing itself.

Go Fucking Do It was new to me, but it’s rather the most brazen and guerrilla version of this idea. The conceit of the service is that if you don’t do whatever it is you supposedly want to go fucking do, then you have to pay a penalty or a ransom of a specified amount. Quit coffee or Go to Africa or Launch my Startup (ugh) are examples the website offers. The insidious thing about Go Fucking Do It, of course, is the idea that anything and everything in life is expressible in monetary terms. Nothing isn’t fungible. In fact, think about where the money goes—to the startup that runs Go Fucking Do It! Giving it to charity “gives users an easy pass” according to its founders. This is a clever and disorienting practical joke, to be sure. It makes me realize how many startups are really more like pranks than like businesses.

Go Fucking Do It

Indeed, perhaps that’s the most important lesson to take from gamification. Games themselves are seen as fungible assets, as a kind of resource one can extract like petroleum from the earth’s mantle, then refine and use as fuel in other contexts—and without altering the experience of game or of play in so doing. This extractionist attitude is pervasive today. Even startups themselves are guilty of it. Nobody at Go Fucking Do It really gives a shit about what anyone does or doesn’t do—they just want to create speculative value that might create attention to leverage into further opportunity. In fact, the creator made it as a part of a perverse “12 startups in 12 months” project, itself an attempt to distill the concept of the startup down to its most refined, artificial rendition. Everything has become a resource that really means to be something other than it appears to be.

MJ There’s an ongoing fervor, if not rapture, today about growing one’s “online brand” under the guise of an unprecedented freedom unleashed by the decentralizing tide of the internet. Prior to the so-called ‘democratization’ associated with social media, the practices of advertising and marketing were professional jobs designated exclusively to a centralized industry of specialists. These practices—upkeep on social media, engagement with comments, staying ‘relevant’, etc.—have taken on an individualized, voluntary and spontaneous character among digital natives. Rather than celebrating this trend as a triumph of ‘disruptive tech’, you lump all the spontaneous activities of self-branding under the umbrella term, “hyperemployment.” By claiming that we are all “hyperemployed,” what kinds of myths are you aiming to dispel? Do you believe we need new mechanisms of remuneration proportionate to the extent of our hyperemployment, or should we understand it more broadly in relation to today’s unemployment?

IB Think about the idea of “flexibility” in the workplace. Making labor more “flexible” in management speak is really just code for making it precarious. Or differently put, it’s the corporation that wins flexibility, not the employee. It takes some balls to present that idea to someone, doesn’t it? To say, well, we’re moving you to a part-time, no-benefits role, but you’ll have the same responsibilities. Just think of all the flexibility this will bring to your life!

In some cases, we’ve begun to realize that we’re not even employed by the organizations that seem to benefit from our flexwork. There’s an aphorism that’s been making the rounds for a few years now: “if you’re not paying, you’re the product.” That is, companies like Google and Facebook that appear to be giving you all these wonderful services for free are really just mining your data to sell to advertisers, their real customers.

But I contend that this is a much deeper matter than just precarious labor on the one hand and data-mining tech business on the other. If you look around, everywhere you turn, effort that was once done on your behalf has become something that you now have to do. Email has made it possible for everyone to handle their own scheduling and correspondence. ERP systems like PeopleSoft have made it possible for everyone to handle their own expense reports. Machine-managed parking meters allow us to pay for a curbside space with a credit card, but they make us wait in line and operate a slow machine for the privilege, in order that newly precarious meter maids can more effectively extract citations by computer.

You mentioned personal branding and social media upkeep. Now we must always upkeep ourselves online, and often our employers or the organizations we participate in. Even people who are lousy at marketing—it is, after all, an actual discipline—are now forced to become bloggers, tweeters, facebookers, and instagrammers to keep their departments or divisions up to date—or just to keep themselves visible. We are all conducting a constant job of full-time self-promotion.

But it’s not just computer systems, either, and it’s not always caused by automation. Simple changes in business practice have these effects too. I’m writing this on an airplane, and when I boarded the flight attendants urged everyone to quickly stow their carry-ons and get out of the aisle on the one hand, but the plane was going to run out of overhead space on the other. Thanks to checked baggage fees, U.S. airlines (which made more than $3 billion in 2013 from such fees) have offloaded the work of handling, hauling, loading, and unloading the bags by charging for the privilege. Meanwhile, we all fly aircraft designed in the 1960s and 70s (and a lot more of us fly, too), so there’s nowhere to put our bags in the cabin in the first place. And on the flip side, the flight attendants themselves are now tasked with dealing with these gate-checked bags and miserable travelers, an effort they wouldn’t have had to endure in a previous era.

Hyperemployment is my name for this phenomenon, the general practice of being constantly bombarded with work that we are obliged, encouraged, or acclimated to do for free, but which has very real costs on our time and our sanity.

MJ You refer to email as an activity originally based on excess and leisure, as being fun, a thing only “done because it could be rather than because it had to be.” The flip side, as we all know, is that it’s (d)evolved into an absolutely mandatory condition of work, to the point where “a whole time management industry has erupted around email, urging us to … avoid checking email first thing in the morning, and so forth.” Do you think this points to a deeper mechanism embedded in our economy, in the relationship between technology and capital? The fact that the same can be said about virtually every new, originally superfluous, communications technology — doesn’t this speak to a general economic tendency? Or is there something fundamentally different with email?

IB Email is a special force in the technology of labor, because it is more like an infrastructure than an activity. Email is the channel through which all other technological prosthetics for capital and labor are directed. Email is a bit like the plumbing of hyperemployment. Not only do automated systems notify and direct us via email, but we direct and regulate one another through email.

But even beyond its function as infrastructure, email also has a disciplinary function. The content of email almost doesn’t matter. Its primary function is to reproduce itself in enough volume to create anxiety and confusion. The constant flow of new email produces an endless supply of potential work. Even figuring out whether or not there is really any “actionable” effort in the endless stream of emails requires viewing, sorting, parsing, even before one can begin conducting the effort needed to act and respond. We usually use precarity to describe the condition whereby employment itself is unstable or insecure. But even within the increasingly precarious jobs, the work itself has become precarious too. Email is a mascot for this sensation. At every moment of the work day—and on into the evening and the night thanks to smartphones—we face the possibility that some request or demand, reasonable or not, might be awaiting us.

If any general principle for technology and capital or labor exists, perhaps it is the phenomenon that email inaugurated: the structuring of latent, “off-line” time as always also being potentially active, working time. Sometimes that work is related to “ordinary” employment—as in the case of email. Other times, it is related to hyperemployment—as in the case of social networking. There’s always some new data arriving, and with it the sense that something valuable and important might be happening. We are now competing with ourselves for our own attention.

MJ A plethora of alternative economic theories have emerged in response to the widespread accessibility and commercialization of the internet, ranging from ‘prosumerism’, ‘attention economy’, to all out anti-capitalism. You alluded to this question by analyzing the corporate information-management game, Attent, which “turns attention into capital, literally, via a scrip currency called Serios … making email more expensive to send, or at least making workers more deliberate about how they do so.” Given the deeply disciplinary regimen that comes with the valorization of attention—the fact that consciousness itself is becoming subject to financial measurability—do you think gaming and play are under threat today by a kind of utilitarian logic? Can games rehabilitate play for its own sake, beyond a reward system, or recapture a notion of value that is irreducible to the economic?

Seriosity’s Attent software simultaneously gamifies and monetizes attention within a company’s email server

IB Critics like Alex Galloway and McKenzie Wark have argued that games are a part of the contemporary obsession with metric- and logic-driven planning and action. Wark gives the name “gamespace” to the modern social condition, under which all activities are destined to be analyzed and optimized, regulated to create the most efficient benefit to agents who, in Wark’s view, amount to the agents of power capable of running or even rigging the game of real life. We are compelled to compete and to win, and to earn ranks and scores that help regulate our status — even if ultimately those goals are empty, meaningless totems.

The problem with an account like Wark’s is that the identification and manipulation of processes in the world does not have to be an intrinsically alienating or meaningless experience. The kind of procedural angst that Attent and gamespace creates alienates because we have little to no ability to participate in the logic that regulates those “games.” It would perhaps be better to call this process one of bureaucratization rather than one of gamification—after all bureaucracy is likewise obsessed with rank and measure, but a measure and rank imposed from above our outside, with which we its agents must submit without negotiation.

Of course, even within the stifle of bureaucracy, it is possible to find little air pockets of gratification. And it’s here, perhaps, that play might ultimately be able to triumph over even the most suffocating of imposed structures. This is the project that David Foster Wallace was working on before his death, and which we can find some evidence for in his published but unfinished novel The Pale King. First Wallace’s bureaucrat acknowledges that “the world of men as it exists today is a bureaucracy,” but that the key to contending with this prison is “the ability to deal with boredom.” Here’s DFW:

“The key is the ability, whether innate or conditioned, to find the other side of the rote, the picayune, the meaningless, the repetitive, the pointlessly complex. To be, in a word, unborable.

It is the key to modern life. If you are immune to boredom, there is literally nothing you cannot accomplish.”

Later, Wallace calls the successful execution of this method heroism: “minutes, hours, weeks, year upon year of the quiet, precise, judicious exercise of probity and care—with no one there to see or cheer.”

So, even in the most aggressively regulated environment, and despite the violence and exploitation that might underlie its regulation, it is still possible to gain leverage on a situation or a system, even in spite of how restrictive and extractionist it is.

From this perspective, the problem isn’t simply the utilitarian logic of games and play as they are often deployed in official contexts. The problem is our continued insistence that there must be something delightful and freewheeling about play and games. That play is a positive experience associated with escaping the world of duty into the world of pure will. And by the way, DFW still held onto this belief in the possibility of pure will—in the ability to extract meaning from within oneself alone, even in the face of the arbitrariness of a situation like a job. In no small part, it contributed to his undoing, that belief in the possibility of secular meaning divined from nothing.

This takes us all the way back to where we started. Rather than thinking of play and games as an expression of the self, we can think of them instead as an activity conducted when faced with specific and particular objects. Play isn’t really about exercising our own will and pleasure as it is attending to the arbitrary but real and undeniable structure of something.

See, when we say “for its own sake” — play for its own sake, or art for its own sake — we really don’t mean it. We mean play for our sake. For the sake of our gratification rather than for the sake of someone else’s profit. But what if we also considered play for the sake of the thing played with? The game or the apparatus or the job or whatever. That play can be done for the sake of things as much as for our sake on their behalf. After all, what if the things are playing us, instead?