The New Metropolitics of Nature

Keywords: biologists, biome, cities, David Gissen, EAB, ecological map, ecosystems, infrastructure, Kat Eshel, Matthew Claudel, metropolitics of nature, Nature, park, Senseable City Lab, smart city, urban, urban ecologies, urban planning

Framing Resilient Urban Ecologies

The New Metropolitics of Nature

By Matthew Claudel and Katherine Eshel

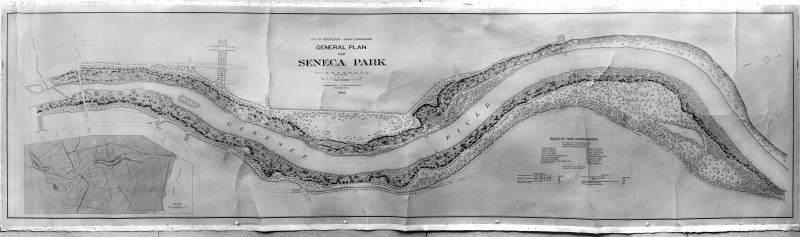

Parks, dog walking, landscaping, ponds. These are the pinpoints of our immediate experience with nature in cities, but far wider, deeper and messier urban ecologies form the skeleton of a sustainably habitable city. Human health is directly tied to those natural urban features and, in the age of the Anthropocene, it is crucial to foster urban ecosystems that are resilient to extreme climate events, slow environmental transformations and that can ultimately adapt to future climate in a stable way (Alberti 2013). The positive impact of nature on city dwellers is clear, from direct use to physical and mental health benefits to general ecosystem services (Wolf). Between air filtration, microclimate regulation, noise reduction, rainwater drainage, sewage treatment, and recreational and cultural uses (Bolund and Hanhammar 1999, Tratalos et al. 2007, Pataki et al. 2011…), nature is incontrovertibly beneficial for cities. However, inviting nature into the city opens political, economic and social debates on implementation, maintenance and basic interactions between nature and urban societies. Moving beyond parks as familiar expressions of urban nature, how might we achieve a truly vibrant urban biome?

The crux of the challenge is the difficulty of valuing ‘nature,’ – without a price tag, it cannot be sold or purchased. Natural elements are expensive to create and maintain and cities with deficits are wary of the vague benefits, particularly when a global agenda of “smartification” is driving global public investment. So-called smart city solutions can be quantified – Intel estimates that Internet of Things alone will see 3.5 trillion dollars-a-year in business, while McKinsey estimates smart urban systems at 400 billion dollars-a-year by 2020 – with impacts in employment, IP, urban services and more. ‘Adding up trees,’ on the other hand, relies on complicated methods like proxies, hedonic pricing, or willingness-to-accept. Valuation of ecosystem services opens a can of ethically debatable worms surrounding the relationship between man and nature – how do you assign a monetary value to the knowledge that there are penguins in Antarctica, or to the splendor of a Grand Canyon sunset (Chee 2004, Wallace 2007,Fisher et al.)? The (in)tangible value of ecosystem services provided by nature ultimately justifies funding eco-initiatives, but cannot be logged into a spreadsheet.

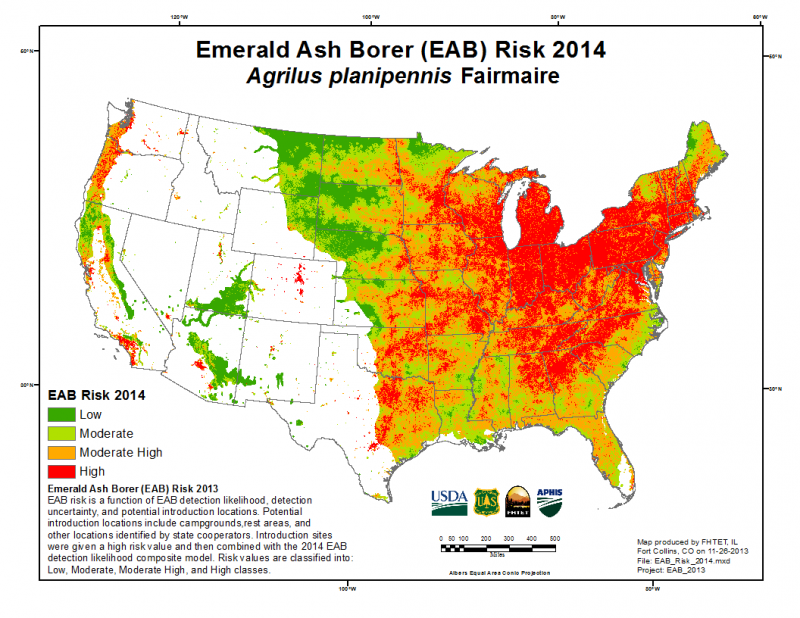

Without a robust cost-benefit analysis, green initiatives often settle for the lowest (justifiable) denominator: one-size-fits-all greenspace policies that sacrifice ecologies of diversity for economies of scale—concrete and cost-effective. From an implementation standpoint, this means a single kind of tree planted many times over, such as the ash trees planted on roadsides throughout the US. What was justified as “beautification” quickly became a regrettable lack of diversity that facilitated the propagation of the emerald ash-borer, an invasive insect that has since stripped streets bare in over 20 states and continues to spread (Herms and McCullough 2013) (see map below of EAB detection risk for 2014).

The emerald ash borer has spread to over 20 states since its accidental introduction to the United States from Asia. At current rates, EAB could functionally extirpate ash trees, with important ecological and economic ramifications. Produced by FHTET, © USDA

Current programs for urban nature involve plants (technically “nature”), but they cannot last; far from solving urban problems, ‘band-aid greenspace’ introduces unbalanced and fragile biomes, as in the case of America’s ash trees. While less economically efficient in the short run, greater planting diversity can promote adaptation and renders urban biomes more resilient (Raupp et al. 2012).

Far from manicured urban parks, diverse and resilient nature is messy, muddy and often unattractive. Architect and urbanist David Gissen has put forward a polemic reconception of ‘urban other’ or ‘subnatures’: the dust, insects, pigeons, mud, waste, and sewage that architecture has traditionally exteriorized. These material flows are actually some of the largest natural systems in the city, and may underpin viable ecologies. In this view, the common distinction between habitable space and environment becomes irrelevant, effectively neutralizing such ideas as ‘throwing away trash.’ Here and away are merged. Gissen “challenge[s] the instrumental value to which nature tends to be relegated in the contemporary city, from the docile greenways of landscape urbanism to the green-washed facades of eco- cities,” (Harrison). If our goal is a sustainably viable urban ecology we must discard the values we assign natural elements.

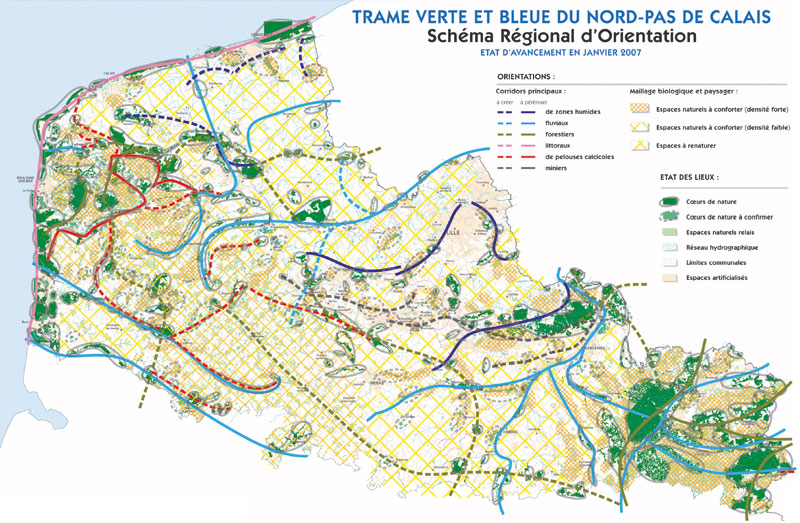

We cannot wait for the government to deliver nature, as if it were a metropolitan utility (see Trames Vertes et Bleues below). The current paradigm of top-down initiatives for expensive but ecologically impotent natural infrastructure must be inverted: to achieve high-value, low-cost and diverse solutions, infrastructure must be non-physical and realized in a distributed way.

France’s Trames Vertes et Bleues (Green and Blue Grid) strategy seeks reframe ecology in the city, as in this regional plan for ecological coherence mapped for the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. The Green and Blue Grid is designed to enhance territorial ecological connectivity by superposing an ecological grid atop urban policy. However, this initiative remains flawed due to its top-down, hyper-centralized planning and implementation structure.

© Institut National de l’Information Géographique et Forestière

Not physical infrastructure, but digital. Not nature delivered, but nurtured.

We propose a new model for urban ecologies. One that takes shape as a dynamic map of existing diversity, opportunities for enhancement – for example, the connectivity of green spaces – and is based on an overarching model for diversity: a projective urban ecology.

Ecologists have a knowledge of the possibilities for urban-nature function, based on diversity, while citizens themselves have the capacity and the willpower to get their hands dirty. Government is uniquely qualified to serve as a mediator between them, laying down the digital framework and setting the tempo of a diverse urban biome. A participatory digital platform breaks from the prescriptive model of ‘utility services’ with an atomized implementation model. In a strong joint venture, government-directed platforms will leverage the power of the crowd to take urban nature from the community garden to the digitally-enabled urban biome. The platform organizes, the citizenry activates.

The process is relevant to biologists and ecologists, but also landscape designers, politicians, architects, transportation officials, and others. The platform will bring together a wide spectrum of experts to set overarching guidelines (essentially, what is native and what works) that frame the participatory and self-sustaining nature-ifying process.

Linux proved the power of the crowd to create software; the next challenge for a globally active community will be to create greenware. In order to thrive, urban natures need diversity, active engagement, and flexibility – exactly the strength of the crowd. Natural ecology must go hand in hand with digital ecology. The seductive aspects of the digital experience – ‘curating’ your online presence – are grafted onto physical locations, hybridizing material and virtual activity. The digital mediates between individual experience and place, and facilitates meshing urban identity with ecology.

This proposed model goes beyond ecological resilience, toward a form of social resilience and sustainability, through a reexamined relationship between citizen and urban environment, building on the success of participative platforms like SeeClickFix and other 311-style apps. In much the same way, citizens reap the benefits directly – both tangible, such as food, and intangible, such as clean air. Furthermore, because the physical implementation is individualized, people feel a stronger personal connection to their environment and a sense of responsibility and ownership.

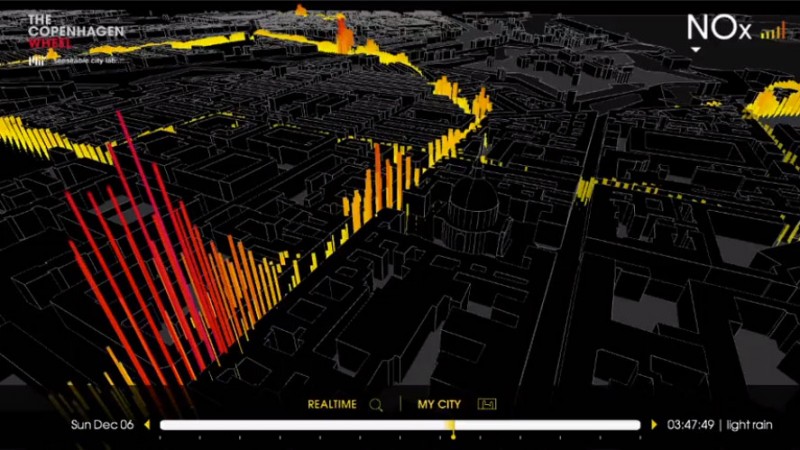

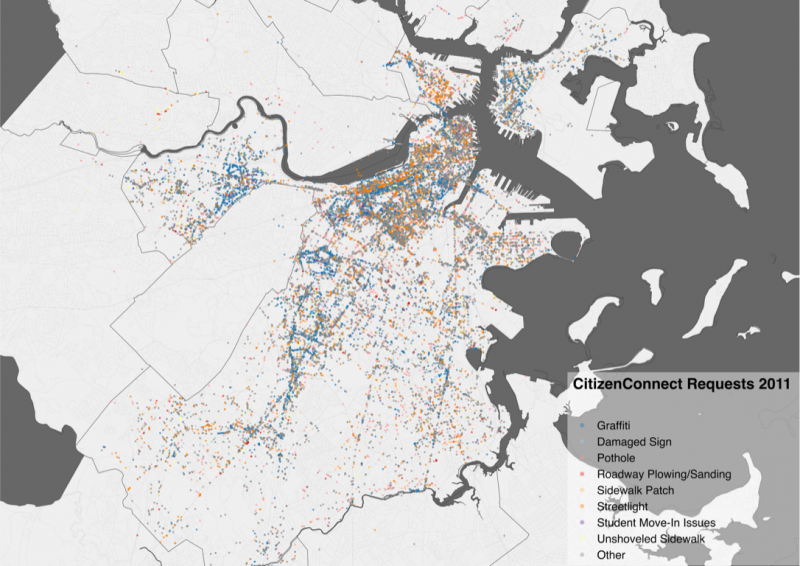

A prototype of government / citizen collaboration has emerged in the form of “311” apps, allowing citizens to report problems in their urban environment and – in some cases – to come together and actively solve them. The MIT Senseable City Lab has mapped 311 reports based on number of calls, response time, and category of complaint.

The projective ecological map can even become a platform for research: the model generates a new kind of ‘big data’: real-time monitoring of ecological diversity as indicator of resilience re-inputted into the map. Building on projects like the Senseable City Lab’s bacteria-based mapping of the city biome by deploying sensors in the sewer system, we might gauge health in the city as well as the status of the flore microbienne – after all, a healthy ecosystem is diverse from megafauna down to its bacteria. This kind of distributed sensing can happen through objective sensors (such as bacteria in sewers) and subjective response (community feedback regarding their individual quadrant of green space). As citizens participate, the platform shows how they value their physical surroundings (both natural and artificial), what natural elements will be most enjoyable, and most importantly, the nature of the interaction between the city and its natural ecology – something that is not yet completely understood.

This government-mediated/citizen-actuated model lays the foundation for future auto-suffisance of natural systems in the urban environment. It is conceivable that this model, as it increases in participation and complexity and effectively ‘learns-by-doing,’ might usher in an independently flourishing urban biome. Meaningful smart city solutions are less about cohesive ‘city-as-computer’ solutions, and more about hybrid platforms that span two axes: bottom-up / top-down and digital / physical. The map of projective ecology that we propose will span those dimensions in a meaningful, resilient and evolutive way. Most importantly, this model is completely feasible today – it asks for more silicon than concrete infrastructure, more investment of time and energy than money. As the process gains traction, citizens not only depend on the city, but the city depends on its citizens, sparking a new metropolitics of urban ecology.