The Trouble with Donelle Woolford

Keywords: 2014, America, american culture, anna soldner s, Antinova, appropriation, april fool's, basel miami, Before the Revolution, bomb, Censored, censoring, Cherise Smith, class, Detumescence, dick's last stand, dis magazine, Discussion, discussiond, donelle woolford, Eleanor Antin, Eleanora Antinova, gender inequality, intellectual, jennifer kidwell, Jeremy Sigler, joe scanlan, joke painting, miami basel, nbc, New York, onochromatic Joke, political, Politics, race, race and class, Richard Prince, richard pryor, Sarah Lookofsky, stealing, taking from others, the richard pryor show, Wallspace Gallery, Whitney Museum

—Joe Scanlan

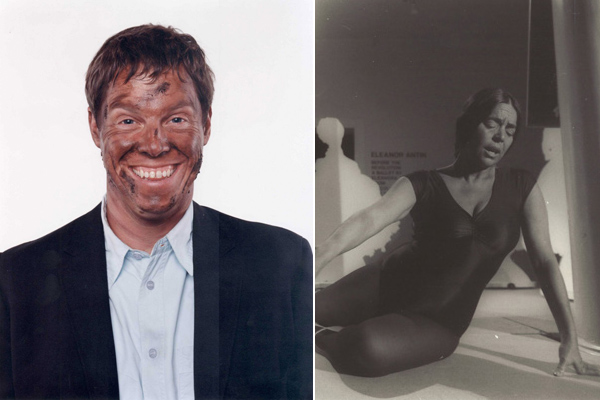

Donelle Woolford, Dick’s Last Stand, 2014, Performance view, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, March 14, 2014, Joe Scanlan and Jennifer Kidwell. Photo: Stephen Garrett Dewyer.

“SEE, WHITE FOLKS TAKE EVERYTHING FROM ME,” cracked Richard Pryor during the opening beats of a notorious television segment taped in 1977 for NBC’s The Richard Pryor Show. Bucking the network that had been censoring his material throughout production to make him acceptable for prime time, the comedian took the stage and announced to a live studio audience that he would perform a monologue as his character Mudbone, a tobacco-spitting, smack-talking sage from Mississippi. As Mudbone, he told biting, unsettling, hilarious stories which, true to Pryor’s form, doubled as potent treatises on race and class in America. He ended the segment by performing a version of himself “for the TV”; in other words, as he believed the network would have preferred him: whitewashed. He stiffened his body and delivered scrubbed-up jokes in a saccharine voice: “I remember the first time I ever heard my father say ‘darn.’ What a trauma, man!” The audience gave Pryor a standing ovation. NBC never aired the segment.

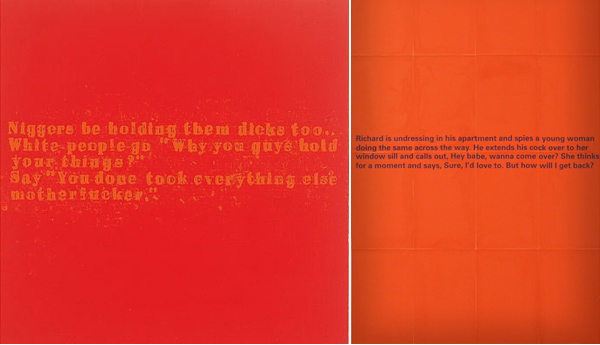

“See, white folks take everything from me,” repeated Donelle Woolford in Dick’s Last Stand, 2014, a reenactment of Pryor’s routine performed this past April Fools’ Day at the Kitchen in New York. Although no program was made available that night, the audience knew, or should have known, that the woman onstage re-creating Pryor’s act was not Donelle Woolford but actress Jennifer Kidwell, hired to perform this character, this pseudonym, this concept of an African-American female artist authored by Joe Scanlan, a white male artist. Staged as part of Donelle Woolford’s participation in the Whitney Biennial, Scanlan’s appropriation of Pryor’s material was intended to align two “dicks” conceptually: Pryor and the artist Richard Prince. On the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum, Scanlan as Donelle Woolford hung two ink-jet prints mounted on canvas—Joke Painting (detumescence) and Detumescence (both 2013)—works that, on the surface of things, satirize Prince’s “Monochromatic Joke” paintings from the late 1980s. Concurrently, an exhibition titled “Dick Jokes” ran in February and March at Wallspace Gallery in New York and featured two rubber tree plant installations as well as over a dozen prints pasted on canvas sending up Prince. Some of the jokes from those works (as well as others) were included in Dick Jokes, a companion book to the shows.

Though an extensive biography states that the artist was born in 1980 in Detroit, Scanlan conceived Donelle Woolford in 2000, naming his creation after the Chicago Bears football player Donnell Woolford. In a BOMB interview with Jeremy Sigler in 2010, Scanlan explained that at the time he had been making abstract wood collages in his studio and realized the work would be more interesting “if someone else made them. . . Someone who could better exploit their historical and cultural references.” Apparently, the art told Scanlan that a black female artist would infuse these pieces with greater meaning. (Scanlan in BOMB: “I studied the collages for a while and let them tell me who their author should be.”) Read another way: Scanlan made art that looked to him like it was made by a black woman.

But seriously, folks: Four years later, in a long Facebook thread regarding Donelle Woolford’s inclusion in the biennial, Scanlan posted that he “invented the character AS a contradiction, in the most basic sense that she is the opposite of myself.” What could possibly be the reason—political, aesthetic, intellectual, and otherwise—for defining and understanding a “black woman” as the opposite of a “white man”? Donelle Woolford, as a site of production (and not a “producer”) simply serves to angle him into discourses in which Scanlan, as a white man, would otherwise have a very different role. A portrait of Scanlan from his Pay Dirt project from 2003 points to an alarming disregard for the shameful history of blackface, and seems to suggest an opportunistic attitude with regard to the subject of race. (Regardless of the artist’s intentions, the best one could say about this photograph is that it’s ignorant of the history of such images).

Left: Joe Scanlan, Self Portrait (Pay Dirt), 2002, C-print, 47 x 35 x 4”. Photo: Walead Beshty. Right: Eleanor Antin, Before the Revolution: A Ballet, 1979–, Performance view: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, October 6–9, 1979. Eleanor Antin as Eleanora Antinova.

Unlike alter egos constructed by artists and collectives to dismantle authorship and distance themselves from a fixed identity, Scanlan’s fuzzy logic that casts a black woman as his “opposite” underscores that the primary subject of Donelle Woolford is in fact Scanlan himself. While Scanlan has not performed as Donelle Woolford, his project functions somewhat similarly to Eleanor Antin’s fictional black ballerina, Eleanora Antinova. Antin embodied, performed, and at times lived as this displaced idealization between 1972 and 1991, sometimes wearing makeup to darken her skin. For the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time events in 2012, Antin codirected Before the Revolution and hired a black actress to play the role of Antinova. (In the play, Antinova declares that she wants to perform as Marie Antoinette, and Diaghilev only allows her to be Cleopatra or Pocahontas.) In reframing the work as theater, Antin crucially distances herself from Antinova: The production is not the vision of a real black ballerina, and the character exists only in this contained narrative. Over the years, Antinova has also maintained a potent ambiguity: As Cherise Smith has noted in Enacting Others, one never knows in these performances whether Antin “distanced herself and Jewishness from the privileges of whiteness by coloring herself black, or whether, by painting her skin dark, she inadvertently aligned herself and Jewishness with whiteness in a troubling albeit ironic, way.”

Twenty-some years after the Whitney’s so-called political biennial of 1993—an edition known for its debates around identity politics—Donelle Woolford stood out in this year’s show as a contemptuous, site-specific backlash. In mid-May the Yams Collective, a group of black artists, withdrew their video from the exhibition, objecting to Donelle Woolford’s “troubling model of the BLACK body and of conceptual RAPE,” an action that stirred up arguments across media outlets and social media platforms. Yet what was also clear was that although Scanlan claimed earlier this year to know nothing of a series of paintings by Glenn Ligon, which bring Prince and Pryor into a conversation, the facts imply otherwise. To begin, Donelle Woolford’s biography includes this listing from 2011:

Sees Glenn Ligon’s mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum. Generally impressed. Of particular interest is a gallery displaying Ligon’s timid foray into a series of penis joke paintings in the mid-1990s. She is delighted that, for whatever reason, Ligon abandoned the idea and its potential.

Ligon’s show was also Donelle Woolford’s favorite of that year:

Glenn Ligon’s midcareer retrospective was a pleasant surprise for me, as someone who has always been a bit bored by the premeditated grit of his black stenciled paintings.

To clarify, the “penis jokes” in Ligon’s early 1990s series—what Scanlan-as-Woolford called Ligon’s “timid foray” are quotes from Richard Pryor routines.

Left: Glenn Ligon, Cocaine (Pimps), 1993, acrylic and paint stick on linen, 32 x 32”. Right: Donelle Woolford, Joke Painting (detumescence), 2013, ink, paper glue, and gesso on linen, 68 x 44”

Whereas Ligon engaged and broadened Prince’s gesture of the monochrome joke painting, allowing Pryor’s rage to seep through, Donelle Woolford’s works are less political and intellectual, and far more personally motivated. A sample joke from the book Dick Jokes:

Richard dies of a heart attack during ArtBasel Miami in the midst of an orgy with three aspiring artists. The mortician tries everything to make Richard’s cock relax but, even in death, it remains erect. As a last resort, Art Basel flies in Andrea Fraser to fuck the corpse, but to no avail—the cock remains stiff. Finally Art Basel calls his wife and explains the situation. She offers an easy solution.“Just cut it off and stick it up his ass,” she says. “That’s the only place it hasn’t been.”

Scanlan found his jokes on the Internet as well as in psychoanalytic texts and other sources. He rewrote his material to cast Prince (and perhaps also Pryor) as “Richard,” the butt of nearly every joke. The humor is good-old-boy bawdy and aggressively regressive; it seems to take down a blue-chip artist and to send up an art world that supports Prince. Scanlan’s strategy falls short, not because his subjects are above a good laugh, but because the puerile jabs fail to provoke new ideas. His aim lacks real conviction, and he reduces what could be a rigorous criticism to a dick joke. In short, the entire project feel like a one-liner. The angle that Donelle Woolford brings to Scanlan’s targets seems to be largely one of deflection, the character serving as a sort of creative protectorate (death of the author this is not). Scanlan still produces art under his own name, work that appears far less contentious than that of Donelle Woolford.

If Scanlan believes that an African-American female artist would become successful with these facile gestures where a white man couldn’t, why? The answer isn’t flattering, as he has imagined a black woman who’s a mediocre Conceptual artist, one with a stunting bitterness toward an art world in which she’s an ambitious participant. Mistaking his apparatus for access, Scanlan via Donelle Woolford also includes this joke in his collection:

Richard runs into his electrician at the local watering hole. After sharing a few beers Richard asks, “Hey, what makes you black men such good lovers?” In an accommodating tone the electrician says,“The trouble with you white folk is that you go in there all rush, rush, rush— and before you know it, it’s over. Now the way us black folk do it, we like to get in there, take it easy, make long strokes, talk sweet a while, stop a while, take our time. Then some more long, slow strokes, nice and cool-like.” Richard goes home and follows the electrician’s advice. After five minutes of lovemaking his wife says, “Hey, how come you’re doing it like a nigger?”

Deluded into thinking that the “voice” of Donelle Woolford would infuse a racist joke with critical valor, Scanlan wills his studio-born fiction to preside over the facts of race and gender inequality, and to slight the very real bodies marked by such jokes. Forging a black woman to perform as both a sword and a shield for male whiteness is neither conceptually astute nor politically provocative. It is simply a toxic reiteration of exhausting appropriation strategies that have gone on for too long in American culture, where taking everything from others is mistaken for creating something new for oneself.