Disability and Disabled Theater

Keywords: ableism, Alice Sheppard, Carrie Sandahl, Dance, disability art, disabled, Disabled Theater, empowerment, Jerome Bel, Lezlie Frye, New York Live Arts, norms, Park McArthur, Performa, performa 13, postmodern, Prejudice, representation, social norms, Theater Hora, theatre

Park McArthur, Lezlie Frye and Alice Sheppard—artists and dancers active in the field of disability studies—respond to Jerome Bel's Disabled Theater.

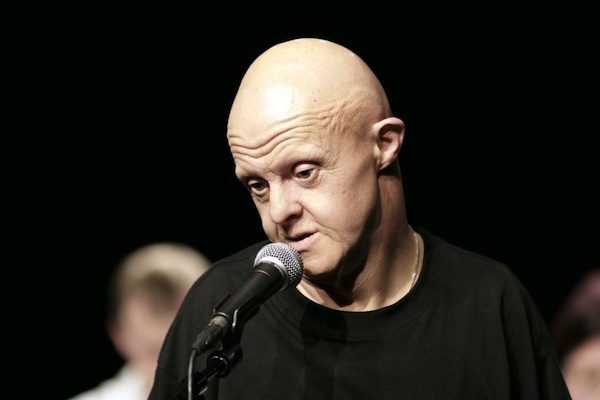

From November 12th to November 17th 2013, Jerome Bel, a French choreographer, and Theater Hora, a company of Swiss actors, presented Disabled Theater at New York Live Arts in partnership with Performa 13.1 Disabled Theater is a compilation of ten dance solos inter-cut by the voice of Simone Truong Michael Manis , a narrator who who sits slightly off-stage and speaks into a microphone (translating the actors’ German into English, narrating the choreographer’s process, and prompting each actor to enter the middle of the stage by speaking their names).

Described variously as “uneasy,” “cathartic,” and “transcendent” in reviews by critics of both visual art and dance, this piece brings together the responses of Lezlie Frye and Alice Sheppard, here woven together by Park McArthur. Frye, Sheppard, and McArthur have distinct yet overlapping relationships to contemporary dance, the field of disability studies, as well as lived experiences of disability. The text is divided into multiple tentacles, an organization form initiated by Sheppard. Calling to mind the multi-headed Hydra, the text is conceived as a poly-vocal resistance to the many ways Disabled Theater transgresses against the disability arts and culture movement: cut off one tentacle and two more grow in its place.

(What follows is deeply informed by conversations among several New York-based writers, filmmakers, dancers, activists, and artists who think, lecture, and write about disability culture, the politics of disability and its representation, following Disabled Theater’s penultimate performance, which was accompanied by a discussion between NYLA Artistic Director Carla Peterson, Jerome Bel, and select performers).

Bel, who, for all his proclaimed belief that “disabled (or incapable!) actors open up new possibilities, new powers” for theater and dance, reveals his willful ignorance of both disability culture the ableist teleology that frames his contributions to Disabled Theater2. His piece—alongside such analysis—provokes a series of yet-unanswered questions about how the radical potential of a cast exclusively made up of cognitively disabled actors plays out, where it is realized, and what limits it comes up against. Among them, what relationships are being dramatized here—among the actors themselves, between Bel and the actors, between the actors and the audience, and between Bel and the audience? What is the impact of Bel’s translated verbal instructions to the performers, and what work does the resulting God-like voice do for the piece? What is the significance of Disabled Theater in terms of how it is perceived, who will ultimately benefit from it, and what meaning will be made by the overwhelmingly neuro-typical (and among them, non-disabled) critics who will presumably attempt to define the stakes of this work?

Tentacle One: Communication

Remo, Gianni, Damian, Matthias B., Matthias G, Julia, Sara, Miranda, Lorraine, and Tiziana: these are the names of the actors who breathe life into Jerome Bel and Theatre Hora’s Disabled Theater. As the first half of the show unfolds, we witness a highly unoriginal ritual that isolates individual actors with cognitive disabilities, engages the saturated technique of staring and being stared at, and ultimately indulges the paradigmatic question, “what happened to you?” Report-backs to the audience—or is it to Bel?—expose each of the actor’s medical histories in the form of a diagnosis, description, or naming of their respective disabilities. These communication rituals of authority and questioning have been historically engaged in freak shows, doctors’ offices, and everyday dramatizations in public space to very harmful ends with regards to individuals, their families, and entire communities. Surely, we are now beyond versions of this fake science and the false knowings of phrenology. Such rituals have been the subject of decades of critical disability art, performance, and theory informed by disability rights activism and studies as well as theory, social movements, and art that critically examines race, gender, sexuality, and a broad range of overlapping identities. The repetition of this historical pattern might, at best, represent an acknowledgment of the thickness and predetermination of the relationship between a single cognitively disabled individual on display and a presumably disproportionately able-bodied and neuro-typical audience. It may, at best, self-consciously raise the specter of this history, outside of which we freaks and gimps, cognitively or physically disabled artists and actors, cannot possibly perform.

So assumedly unknowable is disability to a non-disabled, neuro-typical person that an act of communication is an act of translation–a performance that minimizes the danger of exposure and silences fears of being not understood or not being able to understand. Disabled Theater, for Bel’s sake, is an act of safe and sure communication. As such, the dance is predicated on the assumption of a non-disabled audience. It desires an audience with no experience of disability in any sense. It proceeds as if no one in the audience has a disabled partner, lover, or family member, but is instead encountering disability for the first time. The success of the piece’s communication practice is related only to the willful ignorance that treats disability as difficult to communicate with, separate, and different.

The dance says nothing about disability communication in general: how the actors routinely communicate with each other or the world around them. It says nothing about communication between people with different disabilities. What would Bel say about communication between someone with a visual impairment, a speech impairment, and hearing impairment? How would he understand the political and cultural forces that shape such communications? What would a performance of communication from the actors’ perspectives engender? What could the work have achieved if Bel had asked Theater Hora members about the joys, frustrations, and challenges of communicating with people who assume they have no voice?

Tentacle Two: Disability Arts and Culture

The fact that able-bodied and neuro-typical choreographers and directors like Bel feel entitled to enter into a genre and political domain in order to produce work about a community to which they have no relationship whatsoever—indeed, might even be quite dis-identified from, by Bel’s account—without any sense of obligation to research or explore its history, is cause for concern. On the contrary, Bel and his peers are lauded as brave or “edgy” for traveling into this presumably foreign cultural space, imagined to give meaning to what—and moreover, who—was heretofore considered uninteresting, irrelevant, or lacking. In this way Disabled Theater stokes a cumulative hunger for a deeper engagement with disability and ablebodiedness, nueorotypicality and difference in theatre and across the arts more broadly. It also prompts an honest look at the glass ceiling that excludes many disabled people, people of color—the show notably features exclusively white actors—as well as abundant-bodied or fat folks, gender non-conforming, trans and queer people, and others from the stage and that hides from view the many brilliant artists, dancers, performers, choreographers and directors whose work has yet to be taken seriously in New York and elsewhere.

The worlds of disability culture engage so much more than the question of how non-disabled people interact with disabled people. It also goes beyond therapeutic art and “self-representation” art. The most important artists are not simply creating work in which they see themselves represented, work in which their embodiments, experiences, thought processes, or stories are presented prima facie to an audience. They are using their work to question, challenge, and change. They are creating work that overturns, (sometimes quietly and sometimes with full force), the invisible cultural norms that make our society tick. Disability arts and culture engenders work that is aesthetically and conceptually provocative, theoretically complex, and absolutely critical to our times.

In his lack of relationship to disability history and culture, Bel finds originality in the question of authenticity. He does not recognize how problematic this approach is. The dancers are actors, professional actors who are presumably able to take on characters and characterization. Bel asks them, as one company member Miranda states, “to be myself, my authentic self.” That the notion of an authentic self is highly contested in any discipline that has had contact with postmodern critical theory seems not to register. Even within the context of the piece, the notion of authenticity is problematic. How is an authentic self to be recognized, if it can only respond to the prompts its director deems relevant? Even in non-theoretically inflected theater contexts, the presentation of the person, as opposed to a character is passé, but this seems not to register: for either Bel or its audience. Because the people in question are so widely perceived as not being self-aware, the very possibility of a disabled self suddenly seems intriguing.

Whether or not the selves on stage are fictionalized or performed can not be proven, nor should we wish to find out. Probably some combination of both is true, but the entire mandate is misleading. It does not matter whether or not these were the true selves of the actors; it matters that the setup leaves the audience thinking that this is the case. Because people with cognitive or developmental disability are so frequently seen as childlike, guileless, innocent, incapable of self-regulation, etc., it matters that Bel forces his actors to exist only in this stereotypical field: they can be nothing other than themselves. Perhaps, this could be an acceptable part of the theater, if the art moved through this conceit and on to a different perspective. But when art stolidly and uncritically mirrors societal prejudice, we must ask: who benefits? We have to hold ourselves accountable to enforcing and reinforcing these oppressive social norms.

Tentacle Three: Dramaturgy and Dance

One of Jerome Bel’s choreographic conceits is the portrait solo. Disabled Theater treats its audiences to more of the same, while placing the solo within a framework of a pop culture dance competition. Though dance competitions have supposedly brought dance back into the mainstream, the idea of a competition (Bel having selected a number of solos for presentation to the exclusion of three) resonates differently in a context of disability representation. In the real world of diminishing resources, disabled people have to compete against each other for access to programs, technologies, and support–even in countries with government funded national health services. Postmodern life might be a zero-sum game, but the competitive stakes for disabled life in a postmodern world are higher. Survival. Bel’s dance competition theatricalizes this dilemma without ever offering an avenue for making the social critique explicit.

That said, the movement vocabularies of each of Theater Hora member is utterly compelling, as is the purity of their commitment. Their stage presence speaks volumes, without the need for superfluous translation. Further still, Bel’s mandate of the solo is shot through with connection and partnering. Such acts of resistance establish Disabled Theater as a dance concerning community and relation, despite its best efforts to be otherwise. Disabled Theater–even against Bel’s choreography–substantiates the radical possibility of dance and disability. Members of Theater Hora fill up every inch of space they are offered to express themselves through intuitive movement and performance—sometimes campy, sometimes serious, some more compelling than others, but all remarkably honest—through a landscape of classic musical genres and forms that are easily accessible to the audience. The actors’ dance and music selections range from a Charleston to Abba, from pop music to hand drumming. This is the part of the show in which the cast is onstage together; seated in a large semi-circle spread across the stage, they connect to one another through participation, rootings-on, joining in song by mouthing or singing the words or enacting coordinated dance moves from their chairs, and at times even through the occasional, transparent attempt to draw attention away from the main act and towards themselves. They are actors at the core. Their performance of interdependence, enabled by their presence on stage together, starkly opposes the isolation that marks the dance’s beginning. Indeed, a sense of community and connection crystallizes, even as each actor claims their own, welcome moment to shine.

The quality of this intra-community engagement represents a radical breaking of certain contracts or social norms on stage. In addition to participating in one another’s solo performances in the above-described ways, the cast collectively makes unexpected noises, moves both self-consciously and habitually, tools with objects such as water bottles or personal items, and disperses their attention in a wide range of directions as the show unfolds. As has been suggested by disability theorists such as Carrie Sandahl, among others, these conscious and unconscious performances of disability reshape performance and theater for both actors and audience members alike.

Another moment of radical potential appears when the actors are asked to speak again, this time giving feedback as a form of auto-critique. We hear Bel’s instruction for the actors to comment on how they feel or what they think about the show. Each person comes to the microphone, center-stage once again, and gives voice to their personal experiences, their opinions of the show, and perhaps most gripping, their reckoning with family and other audience members. Some reflections are painful—heartbreaking, even. Others engage humor, and several express enthusiasm and satisfaction with the final product. While some actors express great affection and gratitude towards Bel, one also takes direct issue with his process. Indeed it is this confrontation which prompts Bel to include three more solos, which are inserted into the end of the piece. This segment of Disabled Theater marks an unusual occasion for meta-framing of the work through an integrated collection of cognitively disabled perspectives. Lorraine says that she thinks it’s very good. So does Julia, who makes a request for Justin Beaver, pausing with perfect timing before she cozies up to the mic and coos a demonstrative “Beaver” in her sharp, dramatic finale. Damian says his mother called it a freak show but that she liked it anyway. Matthias G. calls it direct. Matthias B. shares that his sister cried when she saw it, recalling that “she says that we are like animals in the circus: fingers in the nose, scratching, fingers in the mouth.” Tiziana deduces that her sister doesn’t think it’s very cool, but that she likes it anyway. Miranda poignantly reports, “My job in this piece is to be myself and not someone else.” These words are among the diamonds in the rough of Disabled Theater. In other words, when Bel gets out of the way, when his booming, if invisible, voice subsides for long enough for the voices of these ten cognitively disabled actors to emerge in their own rite, the magic of this piece unfolds in an unusually raw and honest way.

Conclusion

Disability is an identity, a practice, a way of making, knowing, and being. Bel does not understand what he does not know. He does not know or care for what he cannot grasp. This is no postmodern failure of language; it matters not that Bel does not know Swiss German. It is rather a critical failure of theory and of imagination.

Not only does Disabled Theater not belong in a world of disability culture, it is a challenge to even consider it a thought-provoking work about disability. Jerome Bel refuses to acknowledge that disability is anything other than pejorative. Bel has repeatedly stated in interviews that disability is not good, not strong, and not able. Given the wide-spread audience reaction of patronizing “awwwwws”, mixed with the decisive booing of Jerome Bel’s comments in his post-performance talk back, we ask: what is generative about Disabled Theater in terms of its impact on dance and theatre in New York and elsewhere? What is the use of such work to disabled actors and performers, artists, directors and choreographers in particular? Does it belong in the genre of disability art, if we have any interest in mapping out the historical landscape that has made room for this piece to emerge and be seen at all, even without being broadly understood in such relationship? What is in fact recuperable about Disabled Theater given some of the limits outlined above? In seeking to unearth the answers to some of these questions, we might best use this work as the wise mirror that it is—not for cognitive disability on stage, but rather for neuro-typical and able-bodied peoples’ ideas, judgments, responses to and engagements with cognitive disability.

- The dance premiered at the Auawirleben performance festival in 2012.

- Quote taken from an interview between Bel and Chiara Vecchiarelli posted on Bel’s website.

Lezlie Frye is an artist, dancer, and teacher based in Brooklyn, NY. She is a doctoral candidate in the American Studies Department, Program in Social and Cultural Analysis, at New York University.

Alice Sheppard is an artist and a professional disabled dancer trained in ballet, modern and contemporary. She has toured nationally and internationally, performing with such companies as AXIS Dance Company, Full Radius Dance, and GDance. Also an academic, Sheppard works in the fields of disability studies

Park McArthur is an artist living in New York City. Her solo exhibition Ramps was recently presented at ESSEX STREET.

"Disillusioned" is a section of DIS Magazine that takes on art and art-related matter that aims to disentangle and dissect how the practices of art might relate to other spheres of production. This partially involves dissolving old assumptions about the aesthetic disciplines, such as discernment, distinction, and disinterestedness, but it will also address how new modes dissolve old forms, allowing for new mechanisms of dispersal, distribution and display to emerge. But more importantly, it will examine how art is increasingly entangled with regimes of distraction, disingenuous affirmation and disposable culture. Disabused will therefore also be a place where arts professionals can express their discomfort and discouragement, even their disgruntlement and disgust; temporarily dissociate from or disown their sites of production; or enact dissent, dissidence, disruption and disobedience. We will do our best to make sure this is all done with the utmost discretion, of course.