THE CRITIQUE OF CRITIQUE

Keywords: conspiracy, criticism, Critique, latour, The Jogging, Toke Lykkeberg

by Toke Lykkeberg

-Salvador Dali

It feels like, for a terribly long time, art criticism has been a critique of various things except art. And the critique that reigns supreme is the critique of capitalism, which pervades all others, since capitalism is thought to pervade everything. A critique of the institution such as a museum is rather often a critique of its sponsors, its board of private collectors, its neoliberal management or its appeal to a broader public, which the critique readily identifies as a mass market. It has been like this for so long that one might think that it has never been any different. Day-in and day-out, art writers, curators and a lot of artists seem to be involved in the same game: to determine whether a work of art is good or bad based on how well it does or does not function as a critique of the capitalist system. And at times reading about art feels like reading the same article over and over again, a feeling that in effect makes you wonder whether you’re actually always looking at the same work of art.

The identity crisis of contemporary art, which can positively be defined as an anything-goes pluralism that ought to compel us to apply specific criteria to specific artworks, dissipates since the critique gathers everyone around the same cause. No matter how unique an artwork might seem at first sight, you instantly have a sense of where a given art writer wants to take it. The conclusion is more often than not the same: a given artwork is said to illustrate that there are larger forces pulling the strings; actually, all of the strings. Either an artwork is hailed as a critique of capitalism or else it is written off by use of a critique of capitalism. When an artwork is hailed as critical, another artwork is often implicitly criticized as affirmative and vice versa. When a performance, for instance, is celebrated as resisting reification and commodification, a painting is as a material object is implicitly written off as giving-in to the market. Though the artworks are different, they get judged according to the same criteria. This critical attitude doesn’t just make for a series of boring reads, it is also cynical though it is thought of as idealistic. In the end, as all self-fulfilling prophecies go, art is all about money, either as a sell-out or as resistance to selling out. The art world thus works according to George W. Bush’s theorem: either you’re with us or against us.

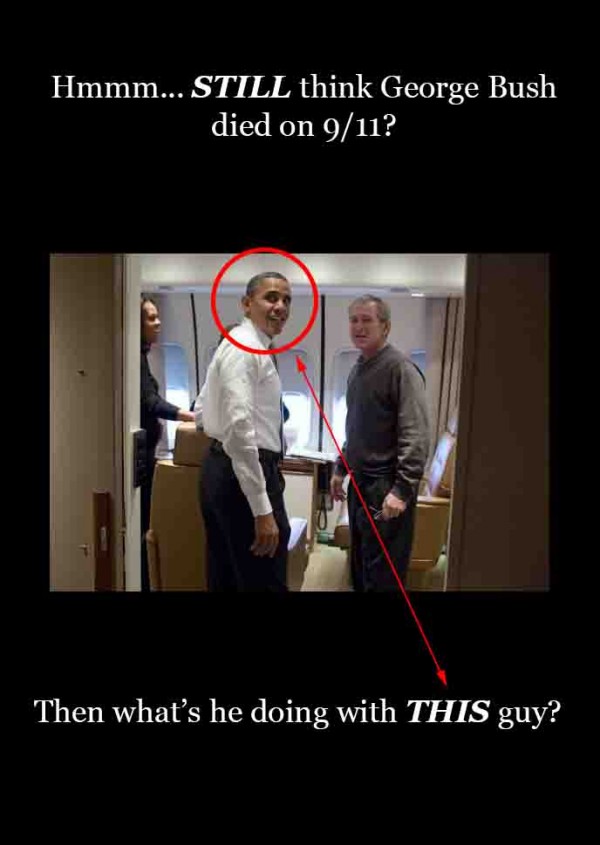

Brad Troemel / The Jogging, WHY IS NO ONE ELSE COVERING THIS?, 2013

Of course, Bush announced those words in the wake of 9/11, an event that has since become a breeding ground for a load of great conspiracy theories. In general, what characterizes conspiracy theories is the ability to explain the workings of the world through a singular cause, i.e. a group of conspirators. Such monocausality is particularly appealing in a world that is difficult to understand; a world that seems more and more complex and opaque while it expands and yet retracts as a “global village”. Monocausality is thus also seductive as a model for understanding that small pocket of the world called the art world, which is highly opaque and best exemplified by a powerful market—one that is exceptionally unregulated and thus most easily manipulated.

I am not in a position to designate a man such as Karl Marx, who jokingly referred to capital as Mr. Capital, as a conspiracy theorist. Nor do I wish to designate his writings as monocausal. As literary critics have pointed out, Marx displayed the construction of his theoretical framework by the obvious use of literary devices1. Maybe he himself foregrounded the postmodern conception of Marxism as one among other grand narratives. However, the more or less ubiquitous critique of capitalism of a Marxist bend underlying most art discourse is not only reminiscent of George W. Bush’s matter-of-fact vision of the world, but overall shares various traits with conspiracy theories as posited by different conspiracy theory researchers. As one such theorist Serge Moscovici has pointed out ”the conspiracy mentality divides people, things, and acts into two classes. One is pure, the other impure, and these classes are not only different, but antagonist (…) Two groups coexist without having anything in common.”2 In the art world, these two classes could be designated as the commercial and noncommercial players and, in more legal terms, the for-profit and not-for-profit institutions and initiatives.

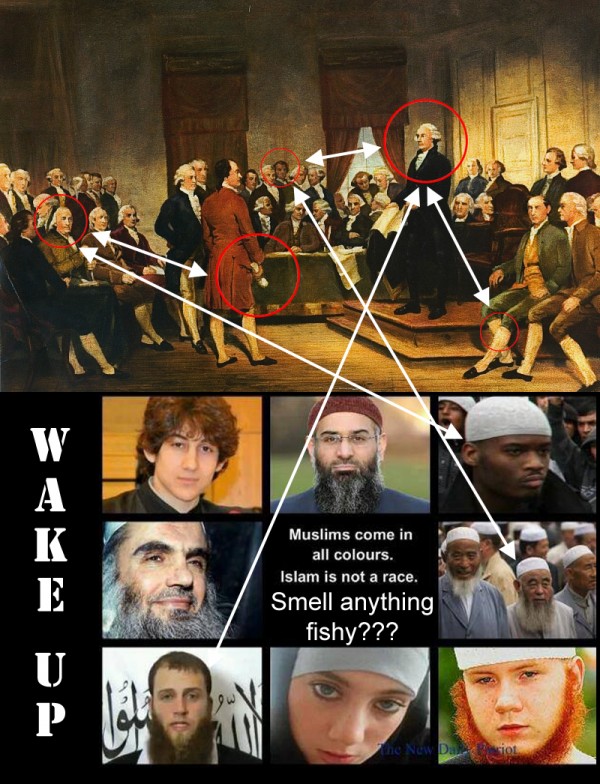

Brad Troemel / The Jogging INTERESTING PARALLELS, 2013

Such binary thinking might seem very strict, but is actually quite unrestricted as it depends on nothing but itself. While conspiracy theories borrow insights from various disciplines, they rely on no one in particular. In the words of another theorist of conspiratorial thinking, Alain de Benoist: “Why struggle with a multitude of historical, psychological and sociological investigations in order to elucidate the meaning of events and the nature of the social, when a conspiracy theory allows one to cling to a unique cause?”3 Likewise in the transdisciplinary art world, many theories are made to service the idea that capitalism runs the whole show. Freewheeling on the back of Marx, art discourse promises to make a coherent whole of that which is not. In the art world, where not only artists but now also curators and other agents are ascribed a high degree of reflexivity, great minds from generation to generation reveal how nothing happens by accident. This mentality is reminiscent of what Carl F. Graumann and Moscovici have been particularly focused on in their conspiracy theory research, namely “the attribution of intention, or more generally, the tendency to think that behind the social movements and changes one is to find creators and transformers of history.”4

Historian of conspiracy theories, Émile Poulat, has tried to define the specific type of reasoning that underpins conspiracy theories: “The imaginary might ‘unreason´, but it reasons always abundantly, with an untiring concern for proofs, quotations and arguments.”5 As an artworlder, it is hard not to identify with the imaginary of the conspiracy theorist. When we the art people ‘get’ an artwork it is normally because we go at it with a good mix of reason and ‘unreason’. To get the drift, we are not necessarily running wild. It is not about pure logic. Nor is it simply touchy-feely. The art crowd rather occupies this middle-ground of bourgeois slackers. Similarly, as Kant suggested, what people on the receiving end of an artwork should get into is the so-called “free play” of their abilities to imagine and understand what they are confronted with. An art experience is governed by certain rules, but it is not guided by them. Kant calls this the “lawfulness without a law” of the art experience. And maybe this is what makes conspiratorial modes of thinking so appealing to artists, from Mark Lombardi to The Jogging. However, in art discourse today, which still works along Kantian lines, this free play is directed towards and determined by a unique cause. While more and more artists explicitly enjoy making artworks that cannot be nailed down by a political program, art writers take even more pride in doing the impossible, namely pinning it down. In order to do so, however, art discourse has to transform the free play into a game which is guided by one rule, but governed by none.

In an otherwise very stimulating essay on the conspiracy images that The Jogging has been churning out for some months now, the New Inquiry editor Rob Horning lets the reader in on his initial dismissal of these whack posts: “It didn’t feel deadpan enough; the irony wasn’t unstable enough.” However, suddenly Horning gets turned on. He is seized by a new reading of what The Jogging is up to: ”But a chapter on conspiracy theory in media scholar Mark Andrejevic’s recent book Infoglut changed my hermeneutic for these images. My epiphany, for what it’s worth, came when I read this: “conspiracy theory, despite its infinite productivity, remains a failure of the imagination that corresponds to an inability to think, in the current instance, outside the horizons of capitalism.” Suddenly a clear-cut interpretation of these images offers itself interlinking the Hebrew alphabet, Red Bull, coconut water, 666 and Hitler: “The images try to simultaneously capture the impossible demands of infinite productivity, for which conspiracy theorizing is an analogue, along with a critique of the consequences of such demands — namely a kind of elitist apathy, a knowing cynicism that expedites capitalism’s flow of goods (artistic or otherwise).” 6

Edward Shenk / The Jogging 1545770_645745712138789_474270858_n, 2014

The aim of this essay is not to rehabilitate critique and the so-called “criticality” of art discourse. Rather it proposes that art discourse find the courage to cool down on critique for a bit, for instance, in order to face and embrace its own identity crisis. This might sound like a demanding mental u-turn. However, the the nature of certain activities in the art world might not change that much since the words ‘crisis’ and ‘critique’ are derived from the same Greek verb ‘krino’ which translates into ‘to separate’, ‘to discern’ and ‘to choose’7. We would still be engaged in discerning investigations, but we would no longer predetermine what art might be dealing with. In the end, art might survive the death of its scapegoat, i.e. capitalism, and live on with other complexities in sight, where the order of the world is not given in advance.

Comparing the workings of art discourse to those of conspiracy theories is not exactly new. Writers of conspiracy theories have pointed out how the practice of revelation and uncovering is ubiquitous in the humanities. French thinker Bruno Latour sees conspiracy theories as a perverse democratization of a critical tradition, which has run out of steam. He suggests “turning the sword of criticism on criticism itself.”8 Other Frenchmen such as Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello have undertaken the task of demonstrating how artistic critique has long been the very motor of capitalism.9 The philosopher Jacques Rancière asks for a “critique of critique”, especially in “the domain where that tradition is still most persistent—art, in particular those major international exhibitions where the presentation of artworks is willingly inscribed in the framework of a general reflection on the state of the world.”10

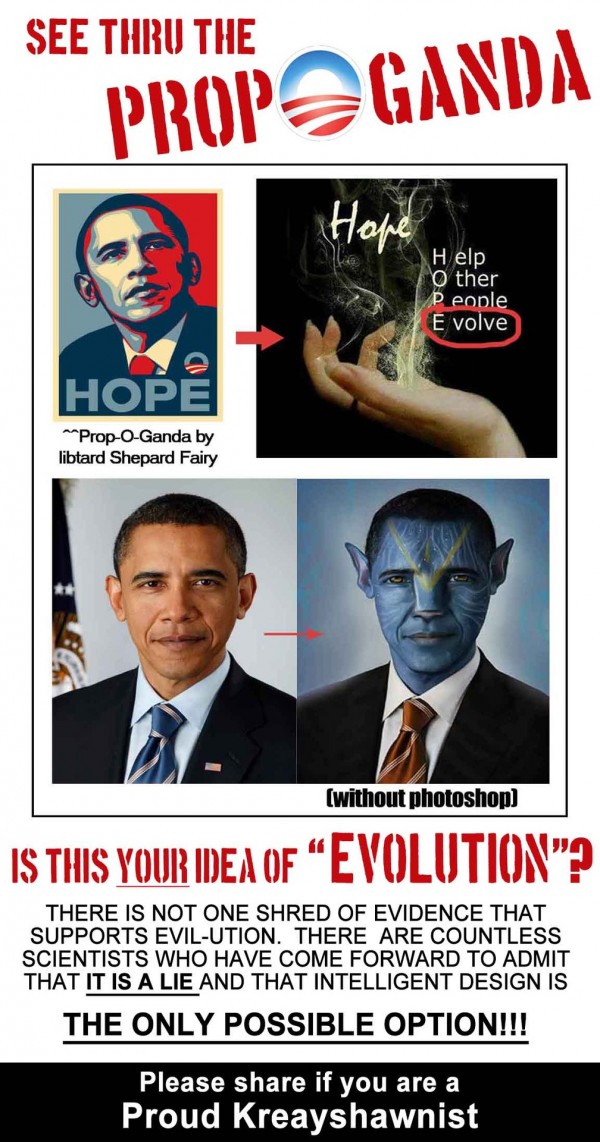

Edward Shenk / The Jogging, proud kreayshawnist, 2014

The hypothesis that art discourse is largely underpinned by capitalist critique and that in effect capitalism pervades everything including art can of course be turned on itself. One might accuse me of being part of a conspiracy that seeks to denounce something as a conspiracy theory. And so could be accused thinkers like Jacques Rancière and Bruno Latour, whose critiques of critique have been dismissed by art historian Hal Foster as “the new opiate Left”. Foster believes that the real problem is actually a lack of critique. In the article “Post-critical” for the Brookly Rail in 2012 Foster writes: “dependent on corporate sponsors, most curators no longer promote the critical debate once deemed essential to the public reception of advanced art.”11 If this is really so, ”corporate sponsors” might not be entirely to blame. Nor the lack of sponsorship itself. If there is no longer any critical debate, it might be because nobody wants to get busted for being a dope dealer.

1 Alex Fletcher, Drop the Satire and No-one Gets hurt: Spectres of Satire in Marx’ Capital in Lanx Satura, 2013

2 Véronique Compion-Vincent, La Société Parano. Théories du complot, menaces et incertitudes, 2005, p. 149

3 Véronique Compion-Vincent, op.cit., p. 151

4 Véronique Compion-Vincent, op.cit., p. 148

5 Véronique Compion-Vincent, op.cit., p. 154

6 Rob Horning, There Are No Accidents, The New Inquiry (as of February 10, 2014: http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/marginal-utility/there-are-no-accidents/)

7 Yves Michaeud, La crise de l’art contemporain, 1997

8 Bruno Latour, Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam ? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern, Critical Inquiry, Vol 30 n° 2, p. 247, Winter 2004

9 See Luc Boltanski & Eve Chiapello, Le Nouvel esprit du capitalisme, 1999 and JEQU, IRL, 2013

10 Jacques Rancière, Le spectateur émancipé, 2009

11 Hal Foster, Post-Critical, December 10, 2012