Josephine Meckseper | The Final Shop

Keywords: Angry Brigade, Baader-Meinhof, Cal Arts, Josephine Meckseper, Mall of America, Occupy Wall Street Movement, Sarah Lookofsky, shopping mall, Situationists, The Complete History of Postcontemporary Art

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, Mall of America, 2009.

Sarah Lookofsky I thought we could begin with a bit of media-specific contemplation. Here we are on a website that addresses, among other things, fashion, a time-bound commodity that your artistic practice has continually explored. I thought it might be interesting to think about this site in contrast with the “sites” you frequently assemble in your work, namely the glass vitrine and display case. The shop window is a curious recreation at this point in time, since people’s desiring (of sex as well as other consumables) and buying have increasingly moved online. To further emphasize this point, the shopping mall, in your piece Mall of America, shot at the once-biggest mall in the world, appears like a heavily discounted ghost land with a few disoriented shoppers milling about, almost as if undead. These pieces seem to recognize that the shop window and its surrounding gigantic mall, once the symbol of American affluence, are, if not obsolescent, then at least obsolescing spatial tropes. What are your motivations for adopting these forms of display, and the often out-of-date stuff you put in them, to problematize our digital age?

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, Mall of America, 2009.

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, Mall of America, 2009.

Josephine Meckseper I shot the Mall of America film just before the recession began in 2007. The focus of the film was to show the iconography of US American consumer ritual in relation to military expansion. The camera zooms in and out of the mall to then focus on an aviation store/military recruiting station. The camera captures the highly propagandistic military images further enhancing the disillusioned atmosphere of the mall. I applied red, white and blue filters to create a sense of alienation and to invert the idea of simplistic patriotism. The notion of desire in the context of consumerism is just another propagandistic mode of manipulation in a capitalist society. The shop window, like the vitrines I make, proposes that such window displays will become archeological relics, and could someday be on display in natural history museums to exemplify life around the turn of the millennium. They are meant to be understood as leftovers of a time before shopping zones and storefronts are boarded up during 99% protests and demonstrators film each other with their iPhones. The digital era does not change the basic function of capitalism to perpetuate production and consumption; only the face is changing. The paradox presented in the Mall of America film recalls Karl Marx’s prediction that capitalism cannot sustain the living standards of the population because of its need to compensate for the deterioration of profit margins by decreasing wages, cutting social benefits and practicing military aggression.

Josephine Meckseper, The Complete History of Postcontemporary Art, 2005.

SL Your practice has maintained a dual preoccupation with consumer capitalism, on the one hand, and protest on the other. Up until recently, these two remained quite disparate in the U.S. context. When large protests happened, as you have recorded, they were mainly against war; they did not imply a broader critique of the economic system “at home.” It seems to me that your work reads quite differently now–differently, say, than it would just 6 months ago. To my mind the Occupy Wall Street Movement is novel in the way it has initiated a systemic critique that attempts to connect the dots between corporate capitalism and politics, both domestic and foreign–hence the proliferation of demands (rather than a lack thereof), from “stop the wars” to “tax the rich”. As far as I can tell, these ideas are starting to make their way into political discourse and the mass media. I wonder how you think about these recent political events, since they seem to relate to the longstanding engagements of your artistic practice in a variety of ways.

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, 04.30.92, 1992.

JM Growing up in Western Germany in the ‘70s, a very similar revolt against corporate capitalism and politics was in motion and had a deep impact on my immediate environment. Namely the Red Army Faction, later renamed the Baader-Meinhof Group, declared war against the “system” — consumer society and the wealthy functionaries of the time. They were calling out for a revolution against capitalism. The fact that they were financed by the East German communist government, which came to light only a few years ago, doesn’t change the motivations of the group at the time. The imagery and sentiment of the leftist revolts of the ‘70s, but also the Situationists and the Angry Brigade (a British libertarian communist militant group in the ‘70s), had a large influence on how I started out as an artist. One of my first films is a documentation of a 24-hour happening with five fellow Cal Arts students on a rooftop in Los Angeles. The idea was to occupy a space, and inhabit it through deliberate action and accumulation of spatial and filmic materials introduced by the group members. It was based on the concept of the Situationist International who advocated experimentation with the construction of situations, namely setting up environments as alternatives to capitalist order. The goal is to point out the central roles of mass media and advertising spectacles in advanced capitalist society in simulating a fake reality in order to mask the real capitalist degradation of human life.

The recent events of Occupy Wall Street reconfirm what I have long argued in my work. I’ve set out to make a case against a celebration of the commercial value of art in favor of the flip side, of revealing modes of production that give voice to protest culture. There is a threshold even in the most complacent society.

Josephine Meckseper, Untitled (Berlin Demonstration, Fire, Cops), 2002, C-Print.

SL Until the recent upheavals across the Middle East, revolutionary change was often assumed to be a thing of the past. While social media received much credit by the media for sparking the Arab Spring, recent political movements–from Tahrir Square to Wall Street–seem rather to prove that social change, regardless of the prevalence of digital communication, still needs to be carried out in the streets and squares of real cities. That of course contradicts my earlier point, and perhaps certain indications present in your work, that city space is over and done for. This brings me to question a prevalent interpretation of your practice, specifically the claim that your work asserts the total commodification of all spheres of human activity: revolutionary protest has become revolutionary chic. I believe I detect more mixed, and less cynical, signals in your work (the footage of street protests in March for Peace, Justice and Democracy, 04/29/06, New York City, 2007, for example, strikes me as more ambiguous). Given the still-unfolding political developments worldwide, would a 2012 vitrine similarly include images of protest within them and references to revolutionary chic?

Josephine Meckseper, The Complete History of Postcontemporary Art, 2005 (detail).

JM The misunderstanding that my work should reference an idea of revolutionary chic probably has to do with a projection of that same audience of how they view their environment. Contrary to this belief, I see my work as a call for street activism, in opposition to a rarified elitist art viewership. My aim is to present consumer display systems that have an auto-critique built within. This can take place, for instance, by inserting images of the opposition produced by capitalist society, namely protestors and rioters, or by using pieces of shattered glass. As a starting point I usually work with films of riots and protests and confront them with forms that refer directly to shop windows smashed by demonstrators. The installations of display forms like shelves and vitrines represent the static face of capitalism. The collective performative aspect of consumption is frozen inside the vitrine and the flip side of capitalism (like images of exploited factory workers) is literally glued to the back of displayed objects. The concealed power structures that are the core of alienated production are made visible here. I have been filming protests in different parts of the world, and they represent a solution in form of action. I question the arbitrariness and entertainment character of news coverage. The films show underexposed civil disobedience and protest; the display works show overexposed modes of consumer society. The images and films I’ve been taking at demonstrations bear witness to the moment when oppositional forces take on a militarized arm of the state, exposing mass media and advertising’s central role in advanced capitalist society.

March for Peace, Justice and Democracy, 04/29/06, New York City, 2007, was filmed at a protest against the war in Iraq. It includes images of federal and court buildings in Foley Square that were recently activated again by the Occupy Wall Street movement. The soundtrack creates a propagandistic brain-washing undertone that evokes the repression of the Bush regime.

Josephine Meckseper Film still, March for Peace, Justice and Democracy, 04/29/06, New York City, 2007.

SL Your most recent artworks have addressed oil production and how the extraction of this natural resource has engendered a close, if largely suppressed, working relationship between governments in the US and the Middle East. Perhaps we can talk about this history as it relates to two of your recent projects? First, your most recent installation, Manhattan Oil Project, brings renditions of 20th century oil pumps to a vacant lot adjacent to Times Square. Here, the past mechanical power of U.S. wealth is brought into a present dominated by Post-Fordist spectacular culture. The depiction of oil here, as a natural resource, reminds us of the fact that the world economy is in fact dependent (to devastating ecological effects, of course) on such material commodities–something that is frequently forgotten in the current focus on pulsating mega screens and stock tickers, the immaterial “stuff” that now supposedly constitutes a solid national economy…

Josephine Meckseper, Installation view, Josephine Meckseper, 2009.

JM I am interested in making the anachronistic nature of oil and gas exploitation visible by taking the oil pump jacks out of context and confronting them with the epicenter of US American entertainment propaganda that Times Square represents. I’m also interested in the role of the artist mistaken as an infantile entertainer of some sort, completely out of touch with social and political cataclysm; a puppet and tool of a capitalist system that rewards mindless subordination and trivial gestures.

When I first exhibited the oil pump sculptures at the Migros Museum in Zurich, they tied into the overall installation that included a military bunker, films and various sculptures portraying a decaying consumer society. They expose the “endpoints” of the United States capitalistic and militaristic crusades since 2001–totalitarianism in the current era of war, globalization, and domestic crisis.

Josephine Meckseper, Installation view, Josephine Meckseper, 2009.

Josephine Meckseper, Fall of the Empire, 2008.

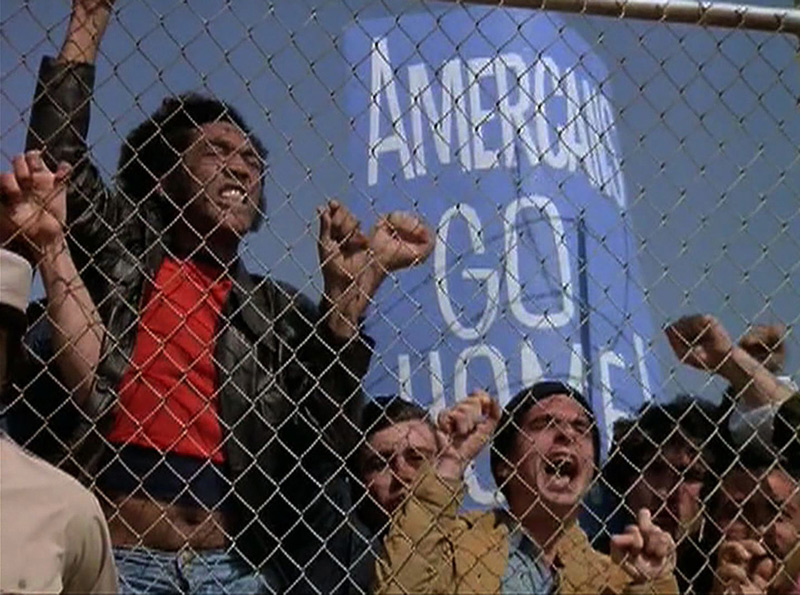

SL The other project I find interesting in this regard is the video included in your The Fall into Time (2011) installation at the Sharjah Biennial, which employs footage adopted entirely from the 1980s TV series Dallas and Dynasty. It includes familiar scenes of cowboy romanticism, luxury goods, New York aerial shots and oil fields, as well as scenes of protest, wherein a screaming crowd (whose members look much more like ‘70s American hippies than Middle Eastern citizens, by the way) is supposed to portray local uproar against Texan cowboys’ meddling in their region’s oil resources. Although this ’80s footage is quite defamiliarizing to contemporary eyes, it necessarily echoes the most recent Iraq War’s war-for-oil charges and the attendant caricatures of Texas cowboys’ oil grab in the Middle East.

Josephine Meckseper, Installation view, Sharjah Biennial 10: Plot for a Biennial, 2011.

JM The film focuses on the glorified depiction of the American oil industry in the light of the economic policies carried out in the early 1980s like so-called “Reaganomics,” which was supporting the wealthy by creating tax benefits and loosening market regulations, while cutting social spending for the poor. The images from the ’80s television shows Dynasty and Dallas are juxtaposed with a Detroit acid house soundtrack from the same decade, creating the context for a renewed debate on offshore oil drilling, the Deepwater Horizon disaster and the recent downfall of the Detroit automobile industry.

At the beginning of the first season of Dynasty, the oil tycoon Blake Carrington has to withdraw his oil company from a fictitious Middle Eastern country because of an anti-American uprising. This very little known scene is the basis of the movie that I created. The film as a whole exemplifies the ruthlessness of the Reagan era, but also ties directly into the present politically motivated struggle for natural resources on one side and a growing revolutionary force on the other side in the suppressed Middle Eastern nations. At the biennial in Sharjah, I found myself navigating the difficult terrain of being a Western artist in the context of a monarchic Middle Eastern country, without seeming condescending or ignorant to the local context. The idea was that the footage of the stereotypical American TV shows would invert this problem by pointing the finger back at Western clichés of entertainment and imperialism.

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, DDAYLNLAASSTY, 2010.

Josephine Meckseper, Film still, DDAYLNLAASSTY, 2010.